Naheed Nenshi was sworn in as Calgary’s 36th mayor on October 25, 2010, was re-elected in 2013, and on Oct. 16, 2017, was re-elected again for a third term.

His parents came to Canada in the early 1970’s from Tanzania, where both sides of his family had lived for generations after arriving there from India. Naheed Nenshi was born in Toronto shortly after his parents arrived. While still a toddler, he and his family moved to Alberta.

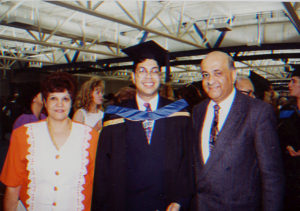

Mayor Nenshi holds a Bachelor of Commerce (with distinction) from the University of Calgary, where he was President of the Students’ Union, and a Master in Public Policy from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, where he studied as a Kennedy Fellow.

Prior to being elected, Mayor Nenshi was with the management-consulting firm McKinsey and Company, later forming his own consultancy business to help public, private and non-profit organizations grow. His diverse clients included the Government of Alberta, The Gap, and the United Nations. He later entered academia, where he was Canada’s first tenured professor in the field of nonprofit management at Mount Royal University’s Bissett School of Business.

For his work, Mayor Nenshi was named a Young Global Leader of the World Economic Forum. In 2013, after his stewardship of the Calgary and area community during devastating flooding, Maclean’s magazine called him the second-most influential person in Canada, after the Prime Minister. In addition, he was awarded the 2014 World Mayor Prize by the UK-based City Mayor’s Foundation as the best mayor in the world.

This spring, Mayor Nenshi was the recipient of the Mosaic Institute’s Honorary Peace Patron Award for 2017, which is awarded every year to an individual who significantly strengthened the fabric of Canada.

We recently had an opportunity to chat with Mayor Nenshi about his own experiences growing up in Canada as a child of immigrants, and about his ongoing passion for building an inclusive and welcoming society.

First, here are a few audio highlights from our conversation, with music by Podington Bear (3:42)

Kolbe Times: First, congratulations on winning the Mosaic Institute’s “Honorary Peace Patron Award” for 2017. From the photos on their website, it looks like the Peace Patron Award Dinner in Toronto was a great event.

Mayor Nenshi: Thank you! And yes, it was a wonderful evening, as well as being a great opportunity for me to speak out on issues that are dear to me. I’ve been very lucky because in this job I have the chance to have a bit of a pulpit. Especially in these divided times, it’s very, very important to use that microphone to talk about pluralism and diversity and inclusion as much as possible.

Kolbe Times: How did your parents come to move to Canada?

Mayor Nenshi: Well, my parents were living and working in Arusha, in northern Tanzania, which is at the base of Mt. Kilimanjaro in East Africa. Then, as now, Arusha was used for lots of international meetings and conferences. Anyways, Dad met some Canadian aid workers. Back in those days they had newspapers delivered to them in the diplomatic pouches. So they got the Toronto Star, and Dad would get a chance to read it when they were done with it. He started learning all about Toronto, and Canada, and he said, “One day I’m going to go and see that place.”

He was particularly interested in the new City Hall in Toronto. I never knew Dad to be interestedin architecture, but he really wanted to see that City Hall, because he couldn’t imagine how you could build such a tall building and have it curve in a half circle. So he always wanted to see it, and when he and my mom got the chance to go to his sister’s wedding in England – I think it was the first time he’d ever been on a plane in his life – he thought, “Well, we’re going abroad anyways, so we’re going to go to this Canada.” And sure enough, they did, and he got to see Toronto’s City Hall.

Times were very difficult at that time in Tanzania, so while they were in Canada they decided to apply for immigration status and stay – and that’s how they ended up living here. Thirty eight years later, after a long story of struggle and sacrifice, my Dad got to sit in another City Hall and watch his son get sworn in as mayor. What I love about that story is that it’s not all that extraordinary. The details might be a little out of the ordinary, sure, but the story itself is very ordinary. It’s the story of a family coming to Canada, and the parents and their kids being able to fulfill really amazing dreams. That’s one of the things that makes this country so special.

Kolbe Times: So you were born in Toronto?

Mayor Nenshi: Yes…barely! My parents had already bought their tickets to England and Canada when Mom discovered she was pregnant, but they decided to go anyways. So I always say I was born in Canada, but made in Africa.

Kolbe Times: And after your parents moved to Toronto, they got quite involved in helping other new immigrants to Canada.

Mayor Nenshi: When they arrived in Toronto, there were only five or six Ismaili Muslim families in Toronto. They formed a little make-shift community, and as all immigrants do, they kind of figured out the system and how to move forward in this country. And then within a year of their arrival, Idi Amin expelled all the Asians from Uganda, and Canada took in many thousands. And by the way, it wasn’t just the Ugandans. When Idi Amin expelled the Ugandans, the Asians in Kenya and Tanzania saw the writing on the wall and many decided that they had better leave, too.

So suddenly my parents and this small community of five or six families, who themselves barely knew how to get on in this country, found themselves looking after thousands of others who had just arrived. There was a lot of work to do, helping to set up support systems that were needed for all the new arrivals. My parents had always had a history of service, so they just kept doing it.

Kolbe Times: And that history of service is also very much a part of your Ismaili faith.

Mayor Nenshi: Very much so. The nice thing is that those refugees were very lucky in one way, because most of them spoke English. A lot of them had gone to English-speaking schools. That made their transition much easier than, for example, the Syrian refugees that we see now. But one of the things that I love is that when the Syrian refugees arrived in Calgary last year, two of the biggest philanthropists in Calgary who stepped up to help them were themselves refugees – one from Uganda and one from Liberia. I thought to myself, that’s such a beautiful expression of what it means to be Canadian.

Kolbe Times: And your family moved to Calgary when you were very young.

Mayor Nenshi: Yes – I always say that I did all my research and prepared the briefing books, and at the age of about 18 months I convinced my parents that the future was in the west. They felt that the folks that they were helping get settled in Toronto were about as settled as they were going to be in the short term, and they wanted to try a new adventure. I had an uncle who was working out here for CP Rail, and they thought it might be an interesting place to try out. So we came out here in about 1973. My parents, with my older sister and me, drove across the country in a Dodge Dart, and started a new life.

Kolbe Times: Tell us some of your childhood memories.

Mayor Nenshi: We spent three years living just outside of Red Deer, but I spent most of my childhood in Calgary, mostly in the NE neighbourhood of Marlborough. It was a great area to grow up in. At the time it was a very mixed community. There weren’t a lot of doctors and lawyers living there, but there were people who were pretty well off, as well as people who were brand new to Canada, trying to make their way. My school had all of that mix, and of course in the late seventies we had a huge influx of students who came from Vietnam. It was one of the waves of ‘boat people’, who really enriched our neighbourhood in remarkable ways. Certainly there were challenges in helping those folks, many of whom didn’t speak English very well, to adjust to life in Canada. But it was a very significant experience that very much influenced my thinking about how we look after people who are newcomers to this country.

I grew up in a family that didn’t have a lot of money, but what we had was a lot of opportunity. I went to great public schools. I would hang out on Saturday afternoons at the public library. I explored the city on public transit, and I learned to swim, very badly, at a public pool. The people who work with me in the Recreation department at the City heard me say that and said, “You know, we run those public pools, and you can take adult swim lessons if you really want to.”

Kolbe Times: So is learning to swim on your bucket list?

Mayor Nenshi: Maybe skating first. I think I was probably one of the only kids on the Canadian prairies who never learned how to skate! But all those memories I mentioned are a huge part of my upbringing, and I lived in Marlborough through my undergraduate degree and through my university years, until I left Calgary for Toronto. I was away for seven or eight years. Since I moved back, I’ve continued to live in NE Calgary, just a little north of where we used to live.

Kolbe Times: As a child of immigrant parents, do you remember experiencing much racism or exclusion growing up?

Mayor Nenshi: There are two answers to that question – one that might surprise people who have never experienced racism – which is “of course.” Every person who is a visible minority in any society deals with that. It’s just part of how you live your life. You know that if you’re driving through certain areas, police officers are going to keep a close eye on you, especially when you’re a young man. It doesn’t happen as much when you’re old like me…or if you’re the mayor. But when you’re a young man, you know that when you go into a big store or whatever, the security guard is going to keep an extra eye on you. It’s just something that you learn to live with.

But the other answer to your question is the converse to this story – you also are living in a place where you have extraordinary, unparalleled opportunity. People often ask me – especially when I was first elected – what did I think of being the first Muslim mayor. I always say that I never in my life thought that there was any job that I couldn’t do in Canada because of my faith. And I still don’t think that there is! Well, I probably couldn’t be a rabbi. But I think that’s the trade-off that you make.

Folks that don’t live that reality are sometimes surprised that racist behaviour exists here to the degree it does, and they’re also surprised that in many ways it doesn’t impact your ability to live a good life. That’s the difficult balance that you have to live with.

This past summer Proctor and Gamble made a video called “The Talk”. It’s about parents having “the talk” with their kids, but in this case they are non-white parents talking to their kids about how they have to work harder at school, about how to talk with the police officer when they pull you over, about how to respond to racist insults…conversations that folks in the mainstream probably have never needed to have. But everyone I know from an ethnic background who has seen that video says, “Well, yeah. Of course we’ve had that talk with our kids.”

And you know, I’d much rather be stopped by the police here in Calgary than just about anywhere else in the world…but this kind of thing still happens here. We have to continue to work on understanding what it means to live in a community that is truly inclusive.

Kolbe Times: So as citizens of Calgary, and ordinary neighbours, and just as human beings – what can we do to make our community more inclusive?

Mayor Nenshi: Today, interestingly, I’ve had three separate conversations over social media with three people who asked me the very same question that you just asked. All three are white men, one of whom is very progressive and thinks big about this, and the other two who are just ‘Average Joes’ raising their kids and living their lives. All three asked me the same question because of disturbing, racist, intolerant things they’ve been hearing about in the news. They were wondering, “Am I complicit in this by my silence? What can I do to make any kind of difference?”

We have to figure out what each one of us can do in order to stand up for the kind of community that every single person deserves. This is very important. We’re at a critical time, I think, in our history. For a long time, we had buried the bitterness, anger and hatred in our community – it just wasn’t polite. We’ve had successive civil rights victories, one after the other, for marginalized groups. And what we’ve learned in a very short time – I’d say in the last 18 to 20 months – is that there is a lot of festering anger and bitterness and intolerance and even hatred that was never far below the surface.

Kolbe Times: We seem to be hearing about that kind of anger everywhere.

Mayor Nenshi: I know. In my own life, I could probably count on one hand or two hands the number of racist or Islamophobic statements that I received in the first five and a half years of being mayor. Now? I receive them every day.

Most of this lives online. Most of it lives anonymously. Certainly it doesn’t cause me to cower under the covers, but it is a marked shift.

It never happens to me in real life. In fact, I can’t even think of one incident since I’ve been mayor when someone said something like that to me in person. But I worry that this permission that people have online is spreading.

This is a dangerous moment. It’s extremely important for the vast majority of us who are decent human beings and who want to stand up for one another, that we do just that. There’s a role for politicians to play, certainly. We have microphones, and we need to use those. But the real change happens when everyday people use their everyday voices, standing up to this stuff – and speaking out for the kinds of communities that we really want and need. We have to speak out for the rights of ALL our neighbours. And I think we’ve gotten a bit complacent.

When you look at those kids in Charlottesville this past summer who were marching for white supremacy, these are kids in their 20s who grew up watching Sesame Street, who have gone to schools with people of every kind of background, and somehow this is the result. We talk a lot about radicalization of young Muslim men. Why don’t we ever talk about how these young white supremacists got radicalized, and what happened, and how we can prevent it? I think we need to have that conversation.

We need to rise above our fears and speak up when we hear someone making a racial comment. And it’s not that hard. We’re lucky because we live in a society where there’s very little cost to being decent. Don’t get me wrong – I know that sometimes there is a cost. Look what happened in Portland, Oregon, where the Good Samaritans who stood up against racial slurs were the ones who paid with their lives. But in the vast majority of social interactions, being the Good Samaritan – playing the role of the protector of others in the community and upholding the dignity of all human beings – is something that has very little cost but extraordinary benefits.

Kolbe Times: What might those kind of actions look like?

Mayor Nenshi: Living in such a multicultural society as we do now, there are lots of opportunities right in our own circles – in the line at Tim Horton’s, or at school, or at our workplace, or with our neighbours on our street. How else is it going to happen?

I get to spend every weekend out doing community events, and the reason I love it is precisely because there is enormous power in simply talking to your neighbours. I’m always pushing for community block parties. In polling data, the vast majority of Americans say that they’ve never met a Muslim – which is obviously not true. They’ve interacted with many Muslim people, but maybe they’ve never actually had a real conversation with one. I think Canada’s very different that way. It doesn’t mean that it’s utopia here, and that everyone agrees with everyone on everything. But I’m talking about approaching one another with an open heart, and believing that everyone deserves the chance to succeed. It’s also about understanding that the success of someone who leads a lifestyle that I might not particularly like, or who belongs to a religion that I don’t understand – their success doesn’t impede my success. That’s the jump we really have to make.

Kolbe Times: So often, it comes down to simple kindness.

Mayor Nenshi: That’s very true. You know, it’s not very popular these days to talk about kindness and compassion and mercy and love. Certainly online you get denigrated for talking about stuff like that. You get called a “snowflake”. But in reality it’s not a sign of weakness – it’s a sign of strength, beyond the imagining of the small-minded and the intolerant. That’s the strength that I think every one of us has to draw upon, particularly in these troubled times.

A big chunk of that is about community service. I have been very, very interested, since long before I was in politics, in civic engagement and community service. When I first became mayor, we launched a program here called “Three Things for Calgary”. For Canada 150, we’ve broadened that to “Three Things for Canada”. And it’s the simplest thing! It’s asking every single Canadian every year to pledge to do at least three acts of community service. That’s it! It can be something small like mowing your neighbour’s lawn – or it can be something big like volunteering with your church or joining a new non-profit organization. It doesn’t matter if it’s big or small. What matters is that it’s an act of service.

I really believe that thousands of acts of service and heroism are what shifts our thinking. It’s thinking about something that’s broader than us – particularly in an increasingly secular world where people don’t have the conventions of faith to help them understand those lessons. We have to figure out other ways to help people think about the “greater good”. When I talk about this to people of faith, it’s easy – they get what I’m talking about. I always say that we people of faith have so much more that unites us than that which divides us: the necessity of service, the aspiration to leave things better than we found them, and the dignity of every human being.

Kolbe Times: You’re in a great position to speak to a lot of people from so many different backgrounds and traditions, and remind them of the things we have in common.

Mayor Nenshi: Yes, and I’m thankful for that, and I don’t take it for granted. One of my favourite things to do is to participate in faith gatherings, whether it’s at a synagogue or a church or a temple. This past Easter Sunday I gave the homily at Knox United Church, and just last weekend I was invited to give a message at a Hindu Mundir. I enjoy opportunities like that so much, and I’ll keep doing it until they kick me off the pulpit.

I’m sitting down in a few weeks with a group of sixty or seventy preachers who represent the Evangelical Christian community. They’ve invited me to come precisely because they want to have a conversation about how their churches can do a better job of promoting inclusion in our city. I love that.

We all need to grow in our understanding that the world is bigger than us, bigger than our own family or our own group…and that we have a role to play in making sure that the world works for all of us.

Kolbe Times: Thanks so much for speaking with us today.

Mayor Nenshi: It’s been great! You’ve touched on issues that I love having conversations about.

Visit www.nenshi.ca

Follow Mayor Nenshi on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram

Photos courtesy of Mayor Naheed Nenshi and family

Quoted and Linked to your article on facebook

https://www.kolbetimes.com/mayor-nenshi/

Mayor Nenshi is retiring as Mayor.

To me he is a true Canadian.

My Favorite quotes:

Kolbe Times: And after your parents moved to Toronto, they got quite involved in helping other new immigrants to Canada.

Mayor Nenshi ” … So suddenly my parents and this small community of five or six families, who themselves barely knew how to get on in this country, found themselves looking after thousands of others who had just arrived. There was a lot of work to do, helping to set up support systems that were needed for all the new arrivals. My parents had always had a history of service, so they just kept doing it.”

Kolbe Times: And that history of service is also very much a part of your Ismaili faith.

Mayor Nenshi “Very much so. … But one of the things that I love is that when the Syrian refugees arrived in Calgary last year, two of the biggest philanthropists in Calgary who stepped up to help them were themselves refugees – one from Uganda and one from Liberia. I thought to myself, that’s such a beautiful expression of what it means to be Canadian.”