Spending time with Sr. Sue Mosteller is akin to basking in sunshine. Her warmth, wisdom and wit shine whenever she speaks, and she has a knack for making a new acquaintance feel very quickly like an old friend.

Mosteller is a Sister of St. Joseph, living in their community in Toronto. Starting in 1972, she spent 40 years as a member of Toronto’s L’Arche Daybreak Community, which is part of an international network of faith-based communities founded by Jean Vanier in 1964. In L’Arche communities, people with and without developmental disabilities live and work together. Mosteller took on a leadership role within the wider L’Arche organization for nine years and travelled to many countries around the globe.

Mosteller was also a close friend of Henri Nouwen, who lived at L’Arche Daybreak for the last ten years of his life. In the introduction to his book The Return of the Prodigal Son, Nouwen describes Mosteller as someone who gave him “indispensable support” whenever things became difficult, and who encouraged him to “struggle through whatever needed to be suffered to reach true inner freedom.” He entrusted Mosteller with his literary estate, and upon his death in 1996 she became the executrix of his literary works.

Mosteller has written three books, received four honorary doctorate degrees, and, at age 83, continues to be a sought-after retreat leader and speaker around the world. We recently asked her to share her remarkable life story, and some of the lessons she has learned along the way.

Audio Highlights from Interview:

Kolbe Times: So let’s start at the beginning. You were born in Ohio?

Sue Mosteller: That’s right. My mother was Canadian and she loved Canada, so she sent us children to boarding school in Canada. When I was 14 years old my father died, and then my mother decided to move back to Canada herself.

Kolbe Times: Your school was in Toronto, run by the Sisters of Saint Joseph. They made quite an impact on you.

Sue Mosteller: Yes, I was very taken with them – I loved them, and as I got older and went through school with them, I decided I wanted to be part of their community. When I was 19, I entered the convent, right out of high school.

Kolbe Times: There must be many lessons you learned, living in community with the sisters.

Sue Mosteller: Many lessons! Life is really about learning isn’t it? I’m so grateful to have been first of all in a family where my mother and father really wanted us to take advantage of life, and to become who we could become. We were taught in the family a lot about living together and getting along and respecting the family and having that sense of “family first”, in a way. Then when I met the Sisters of St. Joseph, I was very moved by their kindness, by their natural way of living. And also I loved their way of being fun, and being religious and being good and wise – and helping me along the way. When I joined the sisters I was of course naive in many ways, only 19 years old and right out of boarding school. Living in community of course is sometimes wonderful… and it’s also sometimes terrible!

I’ve been part of the Sisters of St. Joseph for more than 60 years, so we know each other pretty well. Almost all our lives we’ve been working together, trying to support one another, trying to walk together. I’ve loved it. I don’t have any regrets at all. Life has been very, very good to me. I taught school for 15 years after I joined the sisters. I didn’t have a great aim in life, but the sisters, as I said, were wise, and they encouraged me to teach school. So I went into teaching and I just loved working with young people. It was wonderful. I taught in schools in Kitimat, B.C. and in Ontario.

I think living together in community brings the deep lesson of welcoming the person as they are, and not always trying to change everybody else. Someone once said that our families and communities are often made up of the people we would least choose to live with, if we had our choice! But I have had to learn to let people be who they are, and to find the goodness and the beauty and the depth that’s there. I have had to learn what is important, and what isn’t important. That’s often a journey, because in a family or in a community we’re constantly rubbing against each other, we’re living close together day in and day out…and yet, at the same time I don’t think I would have survived without the support of the people who loved me and carried me through difficult times – they didn’t judge me and or put me in a box.

These are things that I think are very, very significant. You know, we can talk about love, and preach about it, and read about it – but the big challenge is to become love. Now, in my later years, that’s becoming more my focus.

Kolbe Times: In 1967 you met Jean Vanier, the founder of an organization called L’Arche – which is a network of communities all around the world, where people with disabilities, and others who chose to share life with them, live and work together. But back in 1967, L’Arche was still quite new, wasn’t it.

Sue Mosteller: Yes, Jean was living in France, and wasn’t at all well known at that time. His parents were famous in Canada – his father having been Governor General. But nobody really knew who Jean was. In 1967 I was studying at university to finish my B.A., and taking a year off teaching to do that. Studying was not my greatest passion so I organized my university classes midweek so as to have a year of long weekends! I told the other sisters that if they ever needed a partner to accompany them to go anyplace, I’d be happy to go with them. At that time, we never went out alone – always in pairs – and we wore the habit at that time. One day, one of the sisters asked me to accompany her to hear a man from France talk about his work with people who have disabilities. I told her that I wasn’t really very interested, so she should look for someone else to go with her – but if she absolutely couldn’t find anyone else I’d go with her. Well, she came at supper and told me she couldn’t find anyone. And you know, I can still recall that night, even though it was 50 years ago. The moment Jean Vanier started to talk, my heart just leapt. His message was beautiful. It was a key moment in my life. He was actually giving seven lectures, so then I had to scramble around and find partners to accompany me to all of them, because I really wanted to go to them all. And that was the beginning of my journey with Jean.

Kolbe Times: Later you went on a week-long retreat at which he spoke, and again that was very significant time for you. What was it about hearing him that touched you so much?

Sue Mosteller: I think it was the way he talked about Jesus. He seemed to know Jesus as a friend – someone who he talked with every day. I just loved to sit and listen to him speak. Jean still speaks about Jesus as someone that he knows really well, and that’s very rare, I find. People often speak about the life of Jesus, but Jean speaks about him as a close personal friend.

Kolbe Times: Then Jean asked one of the sisters who had done some work at a psychiatric hospital to help him organize a pilgrimage to Lourdes for disabled people and their families. She asked you to help. What was your reply?

Sue Mosteller: I told her that was crazy and that I wasn’t interested in pilgrimages! But as it turned out, we were very surprised that so many people wanted to go, and that the money came, and that we were able to take about 500 people in two planes. We had a blast, and the experience had a very powerful effect on all of us.

Kolbe Times: And it was after you got home that you asked your congregation to let you go live in a L’Arche community called “Daybreak” in Toronto.

Sue Mosteller: Yes, and that was something very unusual at the time. I’m so grateful that they trusted me to go and not live in a convent. At Daybreak, I was living with men and women in the same house, which sisters didn’t do in 1972.

Kolbe Times: What was L’Arche Daybreak like in 1972?

Sue Mosteller: They had a big house that had been a convent and a seminary. It had a lot of bedrooms, and there were 26 of us in that house. They were just getting ready to open a new house on the property. And I went there with a sense of, you know, I can help these poor disabled people. The Bible says, “Blessed are the poor”, so I’ve got to help them because that’s what God says I should do. What a shock it was for me to realize that the Bible didn’t say, “Blessed are those who care for the poor”! I had to get in touch with that reality. These people who I felt I was supposed to teach instead became teachers for me. These people who had suffered so much were people who knew how to forgive in ways that some of us haven’t even thought about. These were people with such generous hearts, who had not been recognized or included, who had been set aside and teased all their lives. They had not been given opportunities to show the gifts that they had! So I grew with that, as I realized that I didn’t have to “take care” of them – I had to help them to evolve so that they could take care of themselves, as much as they were able, and provide their gifts into the community.

So, over the years, we developed a ritual at Daybreak called “Commitment Night”, where everyone makes a commitment to the community. Someone who can’t speak can still smile – so they can welcome our visitors and be present with them. Perhaps someone can help cook, or someone can say grace, or someone can take visitors on a tour. Everyone makes a commitment for the year, and we write that on a chart on the wall so we can remind people of their gifts, and of their responsibilities. So all this was an amazing learning curve for me. I saw the maturity that these people had, and how they were not “scandalized” by weakness. So, if I was having a particularly hairy day and getting all upset or angry about something, well, that’s okay. It wasn’t a big deal. They never held a grudge, or got upset because I was upset.

Kolbe Times: So here were people living together and trying to focus on affirming each other. No one is more “important” than someone else.

Sue Mosteller: That’s right. One of the acts of love that is so key as we deal with one another is to find true ways to affirm each other. We’re all dying for it. We’re dying to hear that we’re okay. We’re dying to hear that we have something of value. But in our busy daily lives, we don’t think to say it or to make sure that the other person knows it or that I see it.

Kolbe Times: You became Community Leader at Daybreak in 1976, and a few years later were named the first International Coordinator for L’Arche after Jean Vanier himself. You held that post for nine years. What was that whole experience like for you?

Sue Mosteller: It was a surprise – and it came with a big learning curve. For one thing, I was scared of flying in those days and the job entailed a whole lot of travel. Not only that, I’m an introvert, so I wasn’t that comfortable being “out there” all the time. Jean Vanier was hugely supportive, plus I had a vice coordinator from France, and he was a gem of a person. And the L’Arche communities and people I visited all welcomed me and made me feel that whatever I was doing was alright; it was enough. So those were things that sunk in for me and gave me confidence to say, “Maybe I don’t have it all together, but people will help me along the way and I have need to learn to ask for help when I need it.” That was an important lesson that I learned – that I don’t have to have my life all together. What I have is enough, and I can lean on other people and invite them into the process, which is what I did. So, I was travelling for about nine years, and it was such a rich time in my life. I can’t even begin to tell you all that I witnessed and learned from the different cultures, different traditions and different religious backgrounds – seeing how people worship together and how they help each other in their spiritual growth.

I guess that the common denominator was caring for each other in community, and people with disabilities being a part of the picture. It was fascinating to see that being played out in so many different cultures.

There are different challenges on the international level. Here’s an example of something that I became aware of during my travels. L’Arche began in France, and the whole thrust for those assistants in France, who were committing to live at L’Arche alongside people with disabilities, was downward mobility. But when we went to India and Africa and Haiti and Honduras, there was a whole different reality. For many of the people coming to live and work at L’Arche, this was the first job they had ever had in their lives. So there were a whole different set of challenges, and the need for enculturation, because we had people coming to L’Arche for the wrong reasons. Everybody needs a job in developing countries and L’Arche would pay their salary – which was never great but was often better than anything they could earn elsewhere.

Another interesting question emerging in these latter years is that some people began to hope for a L’Arche community more in the Islamic tradition. There have been years of dialogue around this, as together we try to understand the ways to call forth the best in another tradition that we might not fully understand. So, there’s a whole question for me of learning to welcome differences, and not see them as a “problem”. We need each other. When I put together a bouquet of flowers, I like to use flowers that are all different, because they’re so beautiful together. We have to recognize the beauty in difference. It’s not a simple thing; it takes time and patience because our first inclination is to want to change others, to drag them over to our side of the fence. It’s all very exciting and challenging. Right now we have a L’Arche community in Syria and one in Egypt, and there are a few others in development. Dialogue is slowly happening – but everyone is happy with the fact that it’s slow, because we want to do this as well as we can.

Kolbe Times: You spent some time with Mother Teresa. How did that come about?

Sue Mosteller: Back in the early 1970’s, before many people had heard about her, I became interested in her work with the poor in India. This was also around the same time that I was just learning about the work that Jean Vanier was doing. Anyways, I got a book contract with a publishing house and went to India and met Mother Teresa, and took photos. Shortly after that I wrote a little book called My Brother, My Sister about Jean Vanier and Mother Teresa. We also invited her to come to Toronto to speak to the Youth Corps, and she stayed with the Sisters of St. Joseph and spoke at Massey Hall.

Kolbe Times: Tell us about your impressions of Mother Teresa.

Sue Mosteller: She was a really marvelous little woman! She had a call to live something very close to God’s people, and she took it right to the end, to the death. But she was a woman of prayer first. I was with her when she prayed, and she was very consumed at a time of prayer; very deeply present during those times. I think from that listening and that connection she knew how to go forward with all the situations that she was meeting. People flocked to help her, which was also wonderful.

Sue Mosteller: She was a really marvelous little woman! She had a call to live something very close to God’s people, and she took it right to the end, to the death. But she was a woman of prayer first. I was with her when she prayed, and she was very consumed at a time of prayer; very deeply present during those times. I think from that listening and that connection she knew how to go forward with all the situations that she was meeting. People flocked to help her, which was also wonderful.

She was someone whose life was integrated between what she was living and what she was saying. That struck me very much. There was an interface there, where neither Jean Vanier or Mother Teresa “preached” at us. They simply talked about their experiences, which inspired us. They didn’t tell us what we had to do; they simply said here’s what I’m doing, and here’s what I’m learning along the way. This is teaching about life in a way that I wasn’t discovering elsewhere.

Kolbe Times: Both Jean Vanier and Mother Teresa had such a strong commitment to helping others.

Sue Mosteller: Yes. And I would say that they had their priorities straight. Too often, I think, we love to run out and save the world and then we find we can’t do that very well. So then we get some people to help us, and then when that all falls apart, we go and pray. In Luke’s Gospel, we see the exact opposite order being played out. It says that Jesus spent the night in prayer, and then he called his disciples together, and then they all went out to do their mission. I think that Jean Vanier and Mother Teresa and Henri started with the primary relationship, their first love, which is the love of God and God’s love for us. After that, they would look for people to join them. And then, finally, they would go out into the world. But that primary relationship, that connection to God, came first in their lives.

Kolbe Times: Another person who had such an impact on your life was Henri Nouwen. Tell us about how you met him.

Sue Mosteller: I was doing a talk at a conference in the early 1980’s in Providence, and he was there also. It was at a time when we were trying at Daybreak to develop a spiritual life in the community where we could worship together with all the different backgrounds and traditions of the people living there. It was a problem for us, because every time we tried to do something we seemed to wound somebody. When I was at this conference, I thought, “I’ll ask Henri Nouwen what he thinks.” So I sat down with him and I said, “You probably don’t know about L’Arche but you know about a lot of things…”, and anyways we had a wonderful chat. He asked me to keep in touch, so we did. We talked maybe three or four times a year on the phone.

Then, as his life and work as a speaker and author developed, Jean Vanier reached out to him and invited him to come to a L’Arche retreat in Chicago in 1984. Henri thought Jean meant come and give the retreat, and he was very surprised to discover that Jean was saying just come and be with us, we aren’t asking you to do anything! Henri later said that nobody had ever invited me to come and not do something. That was very striking for him so he decided he’d better listen to that because he was not happy at teaching at Harvard at that time. So he came to the retreat for three or four days, and spoke to Jean Vanier. He subsequently decided to take a sabbatical year in Jean Vanier’s community in France.

A year later or so later he was asked to come to Kitchener, Ontario to do a wedding. So he wrote to Daybreak and asked us if he could stay with us because he had a 14-day ticket and he wanted a quiet place to do some writing. We said sure, come. It was during that 14 days that one of our people with a disability was hit by a car on Yonge Street. It was a very delicate situation because he had not been properly supervised and the family was understandably upset with us. He was in intensive care, and when Henri heard, he asked to borrow a car and went over to the hospital. The family had asked us not to go to the hospital, which made us very sad because this man had lived with us for eight years and we were very worried about him. Henri kept visiting the man and his family at the hospital, and it didn’t look like the man would live.

At one point Henri asked the father if he had blessed his son. The father said he didn’t know what Henri was talking about and so Henri explained how the Bible tells us that when a child is leaving, a father often blesses his child for the journey. The father started to cry and he said, “I wouldn’t know how to do that,” and Henri offered to help him. So they went into the son’s room in intensive care, and Henri told this father to whisper in his son’s ear and tell him of his love for him. The father started just weeping, telling the son all the things he loved about him. Then Henri told the father to put his hand over Henri’s hand, and together they blessed his head and his hands and his feet for the journey. When they came out of the intensive care room into the hallway, he looked at Henri and said, “Who are you, anyways?” So Henri told him he was a priest and he was staying at Daybreak, and shortly after that the father asked him to tell us at Daybreak that we could come and visit. That night, at Daybreak, Henri asked us to get a picture of our friend and led us in prayers for him, asking each person at Daybreak to tell God why they loved this man.

So everybody in our community met Henri, and it was a very meaningful time because our hearts were breaking for our friend in intensive care, who eventually recovered and came back to live at Daybreak a couple of months later.

After Henri left, we realized we still needed some help and leadership with our problem of trying to worship together. We had people of many different Christian traditions living with us, and three people of the Jewish faith and one person from an Islamic tradition. I remembered that when Henri was visiting us he had told me that he didn’t know what he was going to do the following year. So we wrote him a letter and told him about our ongoing problem with wanting to have a vibrant spirituality that was respectful of all the different people living at Daybreak, but at the same time we didn’t want to water down our spirituality. Well, Henri told us he was thrilled to get our letter, and so he came.

Henri Nouwen (top right), Sue Mosteller and other residents of L’Arche Daybreak. By permission of the Henri Nouwen Legacy Trust

I remember the first time he gathered a little ‘spiritual life’ committee and asked us to tell him about the problem. We all took turns talking how painful it was and how terrible and so on – and then he said, “So, now we have to start a journey. Maybe we should change the word ‘problem’ and call it a gift, and see our journey as unwrapping this gift that God has given us of all the different traditions and backgrounds at Daybreak.”

Henri talked to us about how we needed each other, and that even though we didn’t know how to do this, God would teach us. And so that was the start of a very significant and important time of finding ways to walk together. The other thing he told us was that yes, some people might feel hurt, but it’s okay to be hurt. The important thing is that we have to speak to each other about our hurts. If we water everything down to make sure nobody gets hurt, then we have nothing. So let’s just take our hurts, and live them out together in the process of unwrapping this gift that God has given us – this gift that we don’t quite know how to use. And of course that turns the whole thing around.

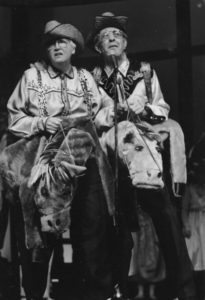

Sue Mosteller and Henri Nouwen in a skit at Daybreak. By permission of the Henri Nouwen Legacy Trust

Kolbe Times: I know from reading some of his books that Henri was a very wounded person himself, but he had such courage.

Sue Mosteller: That’s right. All his life he stayed with the journey. I don’t know how he did it but he did. He was very anguished but he was a genius as well – a troubled and very beautiful fellow. He wasn’t always easy to live with, but we loved him. And that’s the way it is for each of us living in community. We all have our foibles but people love us, so that’s how we survive.

Kolbe Times: Henri had asked you before his sudden death in 1996 to be the literary executrix of his estate. He wrote over 40 books in his lifetime, and his books still speak to us today. And they speak to a whole new generation who are discovering him.

Sue Mosteller: Yes. This year is the 20th anniversary of his death, and we had a large conference at a university where about 30 young people were sponsored to come. They were so moved by his spirituality, and we’ve heard from a few of them who attended who said it was life changing for them. So we’re happy because the younger generation is being introduced to Henri’s legacy.

What a wonderful interview with Sue. Sue is an incredible person and so gifted. She has touched so many lives. Marilyn Moore

So glad you enjoyed the interview, Marilyn. It was so inspiring to spend time with her…and such a joy! We had some good belly laughs together as she told her stories.

I love to hear Sr. Sue speak. She is certainly not “Holier than Thou”, but she loves God, and it comes through in her talks, and it’s great to be around her.

I loved to hear Fr. Henri speak also in his booming voice.

I could also listen to Jean Vanier all day long and more.

What a threesome these people make!!

I totally agree, Rose – what a threesome!