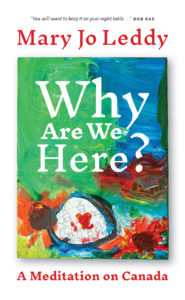

The following is an excerpt from the latest book written by Mary Jo Leddy – theologian, author, activist, and founder of Romero House, a centre for refugees in Toronto. Why Are We Here? A Meditation on Canada, published by Novalis Publishers (2019), offers a moving and thought-provoking portrait of our nation.

The following is an excerpt from the latest book written by Mary Jo Leddy – theologian, author, activist, and founder of Romero House, a centre for refugees in Toronto. Why Are We Here? A Meditation on Canada, published by Novalis Publishers (2019), offers a moving and thought-provoking portrait of our nation.

In the summer, the refugees I live with discover that the direction of hope lies north. This is the time when we, a group of about 50 refugees and their Canadian friends, go for a week-long vacation among the lakes and forests near Manitoulin Island. This is the place which is also known by Indigenous peoples who live there as Turtle Island. However, it is still a new and unknown land to the refugee campers who come from all over the world.

During the months preceding this trip, their first and only experience of Canada has taken place in Toronto, a city where they already feel somewhat at home. They will have studied English and learned something in school about the history, culture and political structure of Canada. This information they have memorized dutifully, carefully.

However, the burden of this obligatory history begins to lighten as we drive north on Highway 400 in a yellow school bus and a caravan of cars, past the suburbs and smaller towns and beyond cottage country until we reach the road leading to Manitoulin Island. For the next week these newcomers will “discover” Canada and will begin to understand why they, and we, are here.

I recall the day at camp when a small group of refugees was led out on a hike following a rugged trail overlooking the North Channel of Georgian Bay. After an hour or more of sweaty hiking over the La Cloche mountain range of white granite and majestic pines, one of the older men, from eastern Europe, climbed up to the top of the promontory, looked out over the far-reaching landscape, raised his hands to the sky and shouted, “Canada, I love you!” In that moment, he took this country to heart.

Later that afternoon, after arriving at their lunch destination on the edge of crystal-clear Horseshoe Lake, some of the kids from the Horn of Africa made their discovery – and their own promises. They were shown a large cliff leaning out over this cool, spring-fed lake. They raced up the slope to the rock edge, glistening, screaming with glee. Then they jumped off, toes pointing down and wings outspread, turning towards the land as they flew, saluting with their right arm to some unseen flag, to this their country, to this their place.

That was the day they became Canadians.

For the past 26 summers, I have pondered this experience they had of the northern wilderness and why it instantly became so important to these young newcomers, most of whom had lived in large urban centres in other countries, many of whom would eventually choose to settle in more populated areas in the south.

In the mind of my heart this insight has slowly taken shape. I recalled that anthropologists have suggested that identity usually takes shape along two vectors: the sense of time and the sense of space. If one of those vectors of identity is weaker, the other becomes stronger in the balancing act of identity. For better or worse, our sense of the timeline history of “modern” Canada is relatively young and even weak.

Four hundred years is neither very long nor epic as the history of nations goes. The history of the Indigenous peoples in this place is longer and more complex by thousands of years. However, many of those histories have been diminished or destroyed, and only now are in the process of being slowly recovered and reclaimed.

In the Canada of the early European settlers and even today, history is a somewhat thin and fragile line of identity.

It is not surprising, then, that a sense of geography and space would and still does become so pivotal for newcomers to this country. In the boreal space of northern Ontario, my refugee neighbours felt that they could belong here, that they could live here and grow here, that they could care for this place. It was not their “native land;’ to be sure, but it had become a “promised land:’ They knew it was the homeland of the First Nations; they knew that people from many nations had settled here before them – and they felt welcome.

They noticed that there were no immigration officers at the entrance to Manitoulin Island asking them to justify their existence. They were no longer in question, and Canada was no longer a question to be answered on an exam. They had arrived not to conquer and own the land, but to live in it. The newcomers caught a glimpse of themselves as inhabitants of this place.

As the kids flew into the water, I saw them shimmer with gratitude in the sunlight. Through the eyes of my eyes I could see that geography was as important as history as a ground for beginning to live here, for belonging. As I watched the kids soar out from the rock and into the sky, I saw my country as though for the first time, in all its spacious splendour. It was a moment when we were, each of us, upheld by wonder, when we all felt grounded, gathered in and free. It was a moment of original gratitude.

These have been moments of grace in my summer meditations: precious times when I have taken a second look at the country called Canada. The people from elsewhere – and from here – have taught me how to say thank you in many different languages: Gracias, Shukran, Miigwech . . . thank you to the trees, to the waters, to the animals, to the First Peoples, to the early settlers, to my ancestors who came on coffin ships from Ireland to survive, to all that is living, growing and giving and here.

For more information about supporting refugees in Canada, visit www.romerohouse.org