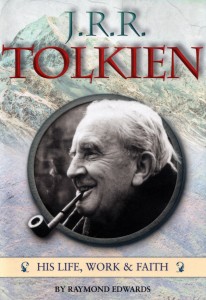

A review of J.R.R. Tolkien: His Life, Works and Faith (2012, CTS Publications)

I can still remember my “Lord of the Rings” summer. It was the summer after grade eleven, and i was getting sick and tired of high school. I had lined up a steady but rather boring waitressing job, and one day I picked up The Fellowship of the Ring, the first book in J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, at the public library. From the first chapter my little world – and my summer – was transformed. I devoured all three books in the trilogy over those two hot, dry, languishing months. Though my body existed in the world of waitressing and hanging out with friends and family, I LIVED in Middle-earth.

Flash forward to the years 2001 to 2003 when I, along with millions of others, blissfully trotted to the theatre to watch all three blockbuster “Lord of the Rings” movies directed by Peter Jackson. And last fall, with the release of “The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey”, I was again happily plunged back into Middle-earth. Last fall also saw the publication of a new short biography of the man who has brought such enjoyment to fans like me around the globe.

J.R.R. Tolkien: His Life, Work and Faith, written by Raymond Edwards, tells the fascinating tale of how a young British boy, orphaned in 1904 at age thirteen, came to write books that, one might argue, kicked off the genre of fantasy fiction.

The book begins with a vivid description of a makeshift hospital set up in a university hall in England in 1916, filled with sick and injured soldiers home from WWI. One young soldier spends most of his time scribbling in a small notebook “stories of an age of myth, of elves and dragons and love and despair and hope lost and renewed. His name is Ronald Tolkien.”

The stories Tolkien wrote in that hospital cot were not published for many, many years, but it was here that his life’s work began. Edwards’ book recounts Tolkien’s early family life and how, after the death of his parents, he and his younger brother became wards of Father Francis Morgan, a family friend. Tolkien himself later called Fr. Morgan his “second father”, and, upon hearing the news of Fr. Morgan’s death in 1934, Tolkien wrote to his friend C.S. Lewis: “I feel like a lost survivor in a new alien world after the real world has passed away.”

Tolkien went on to marry and raise a family of four, and also become a world-renowned scholar of ancient languages. But it was in the informal literary club called The Inklings, formed by Lewis, where his fiction writing blossomed. Tolkien first met Lewis in 1926 at Magdalen College in Oxford, where they both taught, and the book thoroughly describes the arc of their long relationship. Many of Tolkien’s stories, written to entertain his children, might never have developed into anything else if not for Lewis. As Tolkien himself wrote, Lewis was “for long my only audience. Only from him did I ever get the idea that my “stuff” could be more than a private hobby.” Edwards also details how Tolkien’s early Catholic formation shaped his writing, which was also infused with his love of heroic legends from Northern mythology.

Edwards book does more than narrate the intriguing facts of Tolkien’s life – he also provides us with thoughtful insights into the man and his times. He writes, “Tolkien’s writing is rooted, certainly, in his vast and intuitive scholarship, but also in an imaginative reaction by an acutely sensitive and educated Catholic to the staggering trauma of the Great War. Running through his work is a profound and often heartbreaking meditation on the ruinous perversion of goodness and civilization, on the coterminous arising of aching beauty and unblinking malevolence from the same God-given faculty of sub-creation.”

Though a small book – almost pocket sized and only 93 pages long – it is a delight to read and should not be underestimated…which reminds me of something Gandalf once said about a little friend of his: “There is more to this hobbit than meets the eye.”

Quotes from the works of J.R.R. Tolkien:

The Fellowship of the Ring

The wide world is all about you: you can fence yourselves in, but you cannot forever fence it out.

– Gildor Inglorion, Elf

All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.

– Gandalf

It is perilous to study too deeply the arts of the Enemy, for good or for ill.

– Elrond, Lord of Rivendell

The Two Towers

There are some things it is better to begin than to refuse, even though the end may be dark.

– Aragorn

It’s like in the great stories, Mr. Frodo, the ones that really mattered. Full of darkness and danger they were, and sometimes you didn’t want to know the end because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end it’s only a passing thing, this shadow; even darkness must pass. A new day will come, and when the sun shines it’ll shine out the clearer.

– Sam Gamgee

The Return of the King

In sorrow we must go, but not in despair. Behold! We are not bound forever to the circles of the world, and beyond them is more than memory.

In sorrow we must go, but not in despair. Behold! We are not bound forever to the circles of the world, and beyond them is more than memory.

– Aragorn

I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them.

– Frodo Baggins

The Hobbit

Saruman believes it is only great power that can hold evil in check, but that is not what I have found. I found it is the small everyday deeds of ordinary folk that keep the darkness at bay… small acts of kindness and love.

– Gandalf

Great review, Laura.

Thanks – it was such a great little book!