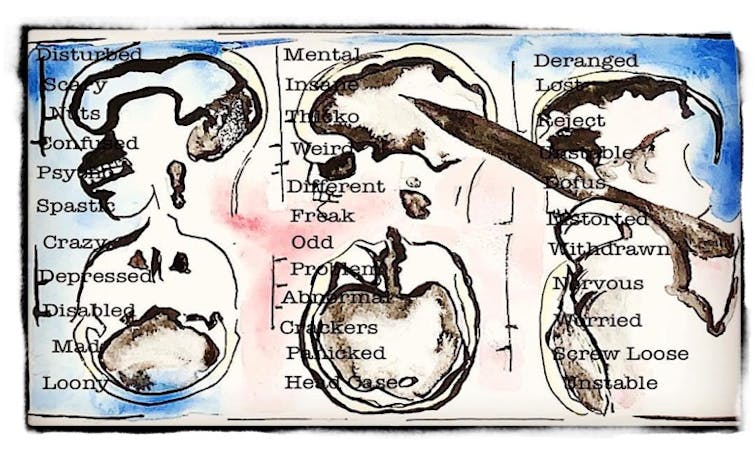

‘Crazy Brain’ by William Doan

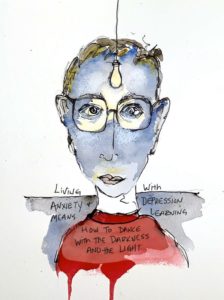

I’ve lived much of my life with anxiety and depression, including the negative feelings – shame and self-doubt – that seduced me into believing the stigma around mental illness: that people knew I wasn’t good enough; that they would avoid me because I was different or unstable; and that I had to find a way to make them like me.

It took me some time – I’m a classic late bloomer – but just before I turned 60, I discovered that sharing my story by drawing could be an effective way to both alleviate my symptoms and combat that stigma.

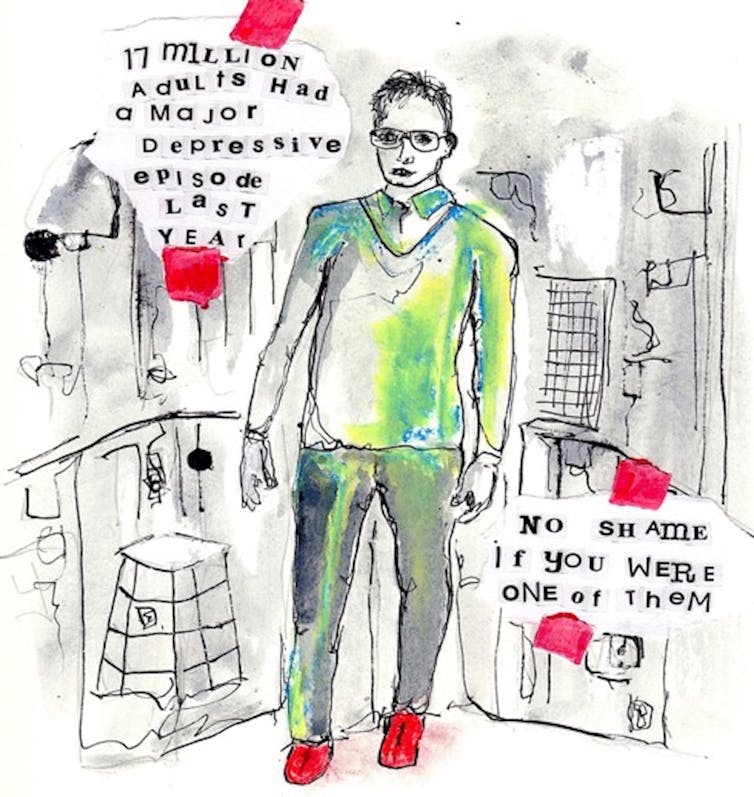

Mental health disorders are complicated. There are 22 sections of criteria and codes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – and that’s just for anxiety. Meanwhile, the psychiatric literature on depression is enormous, with hundreds of scholarly articles and books published in the past two years alone.

One thing we seem to know for certain is that, somehow, anxiety and depression made it through the evolutionary process.

“Since antiquity,” writes William Styron in Darkness Made Visible: A Memoir of Madness, “in the tortured lament of Job, in the choruses of Sophocles and Aeschylus – chroniclers of the human spirit have been wrestling with a vocabulary that might give proper expression to the desolation of melancholia.”

My first anxiety attacks happened early in life. By the time I was 13, I knew the signs: quickened breathing and an increased heart rate, blurry vision, sweaty palms, and sudden fight or flight impulses. Once, when on deck to bat in Little League, I became so panicked I dropped my bat and fled the ball field. I rode my bike all the way home, barely able to see five feet in front of me.

Growing up, I also spent countless hours drawing. I drew or scribbled on every scrap of paper I could find, and I copied those funny characters that appeared on the back of each week’s issue of TV Guide. While I took one art class in high school, I was mostly self-taught. I always knew I loved to draw, but I never wondered why. It was just something I did.

As I grew older, I continued to suffer from panic attacks and depressive episodes, which I managed to hide from others. I eventually became a theater professor at Penn State University, where I still teach today. In addition to teaching history and literature, I make autobiographical solo performance pieces. But in 2014, my sister died after spending two years in a vegetative state due to a traumatic brain injury. It was as if the one thread capable of unraveling my entire life was pulled.

Drawing became almost an obsession.

I did over 200 drawings of my sister and eventually created a play and solo performance piece titled “Drifting.” I visually archived her journey to death. In the midst of this, I started what became the Anxiety Project, which now contains over 500 drawings and two performance pieces. I didn’t really think too much about its purpose. I just knew I had to make drawings about anxiety and depression.

I made a lot of this work without any initial plans to share it. I was just trying to survive. As I slowly began to share some of the work, there was a strange mix of relief from sharing my feelings and dread that the work would ultimately fail to mean anything to others, or that people would think I was crazy for making this kind of work. (These same feelings have cropped up while writing this article.)

And then I pretty much crashed. I still couldn’t emerge from my grief or separate it from my ongoing struggles with anxiety and depression.

I was in trouble. And I knew I had to get help. So I started to tell my wife and family the truth – that this struggle went beyond the death of my sister, that for most of my life, I had been in an almost constant battle with anxiety and depression, and that I was afraid I was finally losing and might go crazy. I found an excellent therapist. I started doing the hard work of living with my anxiety and depression honestly and openly, which, for me, includes taking an antidepressant. Acknowledging and accepting the need for medication was perhaps the most difficult stigma to face. I felt like a failure. Getting past that feeling took some time.

Living openly with my anxiety and depression has helped me better understand my drawing and creative work as efforts to make meaning out of the volcanic feelings of fear and despair – and the almost catatonic shutdowns that could happen inside me at any time.

This new understanding eventually led me to become intentional about drawing as a way to imagine myself as mentally healthy, rather than define myself by my mental illness. I drew upon the work of artists like Frederick Franck and his books The Zen of Seeing and The Awakened Eye, which outline simple meditative approaches to drawing.

I work almost solely in ink- and water-based mediums because of the gestural and fluid ways I can translate feelings into lines and movement of color. I draw every day, and sometimes I’ll simply draw what I see – birds, flowers, landscapes, people, myself – to stay grounded in the here and now.

‘RoseHips Meditation’ by Wiliam Doan

Sharing what it’s like to live with anxiety and depression feels like undressing in front of strangers, but I thought it might help decrease stigma, which nearly 90% of people with mental health problems say has a negative effect on their lives.

As I learned more about the connection between drawing, wellness and stigma, it turns out that I was onto something.

In 2016, psychologist Jennifer Drake and her team of researchers studied the benefits of drawing over four consecutive days, and discovered that the simple daily act has benefits. “You can get a positive effect with just 15 minutes of drawing,” she concludes. “Drawing to distract is a simple and powerful way to elevate mood, at least in the short term.” Meanwhile, researchers across many scientific fields have explored the ways art making can combat stigma about mental illness.

As Jenny Lawson writes in Furiously Happy: A Funny Book About Horrible Things, “When you come out of the grips of a depression there is an incredible relief, but not one you feel allowed to celebrate. Instead, the feeling of victory is replaced with anxiety that it will happen again, and with shame and vulnerability when you see how your illness affected your family, your work, everything left untouched while you struggled to survive.”

For me, it was the kind of shame that shepherds you right into the waiting arms of the stigma around mental illness. I needed to find a way through – for myself and, hopefully, for others.

Art became the way.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.