Harmony through Harmony (HtH), founded in 2009, is a choral organization with a difference. Today, three ensembles with a total of 35-members, uses its collective voice to raise funds and awareness about social justice issues, while also developing the leadership skills of its members and building community. HtH members, who are between 18 and 35 years old, meet every week for dinner, book study, discussion and rehearsal.

Harmony through Harmony’s vision is to follow Christ’s example to discover how each of us can be a voice for the voiceless. Since their inception, the group has helped to raise over $300,000 for a variety of causes and organizations. Their efforts have frequently been focused on the issue of human trafficking and sexual exploitation.

The group travels to places where “traditional” choirs don’t normally go. Last spring they completed a cross-country tour, which took them to Hollow Waters, an Ojibwe-speaking community north of Winnipeg. Executive Director Beth McLean Wiest writes about the choir’s experience of spending time with Marcel Hardisty, a community leader at Hollow Waters.

Connections, Old and New

Marcel Hardisty is a wise and humble man, passionate about his people and their healing and a firm believer in restorative justice. He is an Aboriginal Community Sexual Abuse Intervention Specialist, and past president of Community Holistic Circle Healing – a comprehensive networking and healing system. Along with our friend Steve Bell, we were eager to spend time learning from Marcel. The first day began with a teaching about the Anishinaabe philosophy.

Anishinaabe means “First Man” or “Original Peoples”. They are a conglomerate of the tribes of Odawa, Ojibwe and Algonquin peoples, who speak closely related languages and live in the area surrounding the Great Lakes. Before the residential schools, the people understood what it meant to be Anishinaabe. Tragically, many no longer know this part of their identity. Those who do, like Marcel, are doing their part to educate others in hope that one day soon their people will all understand what it means to be Anishinaabe once more.

For me, the loss of identity was a sobering thought. What would it be like for me to lose my identity as a Canadian? I am proud to be Canadian and as I have traveled the world I am proud of how others view my country. The Anishinaabe people have been here longer than any of us. What went so very wrong for them to lose their identity? The answer to that question is one that humbles me and brings me to my knees.

As Marcel explained, to be Anishinaabe means to understand that we are all created and need each other. Creator will always provide all that you need for your life, which all comes from the raw material of Mother Earth. Take only what you need. Creator made the first family: Mother Earth, Grandmother Moon, Grandfather Sun – and then made the first children: plant life, four leggeds, birds and fish. Creator then made his most prized creation: Woman. Sounds a lot like the creation story that I was raised with.

Marcel then went on to enlighten us about the seven laws that the Anishinaabe live by. The seven laws teach how to live with all of creation, especially other human beings: respect, humility, truth, courage, wisdom, honesty and sharing. When we don’t live by these seven laws, we are creating chaos, destruction, death. Whatever happens to the earth happens to the people.

Anishinaabe philosophy says that you belong to community and community belongs to you. A key teaching in the stories that First Nations tell their children is this: Do not get ahead of the community. Why? Because relationship is sacred. Since relationship is sacred, the Anishinaabe perspective is that our ancestors are always with us. Heaven is not far – just over here at arms’ reach.

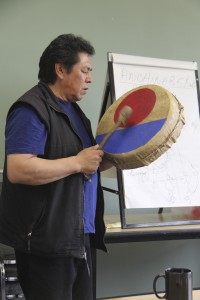

Marcel shared an “honour song” with us, to honour the ancestors. He sang with his drum. It was sacred to hear him, watch him and imagine what the words were about. I love how music communicates messages at so many levels. We then sang one of our songs for him as a way to honour him sharing with us. And again, it was a sacred moment.

Learning about honouring ancestors was a big “ah-ha!” moment for many of us. Honouring ancestors is not necessarily ancestral worship; it is recognition of our emotional / mental / spiritual / physical whole self in interaction with creation, with community, with our past, with eternity, with Creator.

It seems to me that as Europeans, we have lost touch with our stories. We have lost the understanding of sacred. We have lost our identity as a whole person. What the aboriginal people refer to as ancestors would be what Christians refer to as saints. Consider this – those who are closer to God are more capable of being active in our lives. There is nothing distracting them from being everything that God designed them to be.

Marcel opened our eyes to a new way of looking at Canada, but it was also a critical moment in the Harmony through Harmony journey – a point we look back on and see as a “crucible moment” for us as a community and as individuals. We are thankful for the challenge that he gave us. We appreciate his openness to making a connection and helping us to learn. I hope that we have the heart capacity to do the same for others.

Harmony through Harmony – “Baby”

Harmony through Harmony – “Sing Out”