Through the generosity of 94 year old Lil Faider, a tireless advocate for interfaith understanding and cooperation, Beth Tzedec Congregation in Calgary has been offering a unique opportunity to explore the fundamental values and observances of one major religious tradition each year. Since its start in 2013, the Lil Faider Interfaith Scholar-in-Residence Project has included representatives from Sikhism, First Nations, Islam, and Buddhism. Each in turn presented a year-long program of learning experiences that have allowed for a deeper appreciation of their faith. Rabbi Shaul Osadchey and the Beth Tzedec community have embraced this very enriching bridge-building experiment.

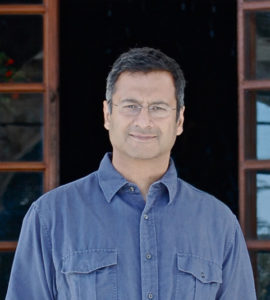

The fifth and current Scholar-in-Residence is Dr. Tinu Ruparell. He is thoroughly enjoying this chance to engage with members of the Beth Tzedec Congregation, as he leads them in an exploration of the history and teachings of Hinduism, with lectures, discussions, and other events such as film screenings and a visit to a local Hindu Temple. The public is also welcome to take part in these activities.

Here are Dr. Ruparell’s reflections on crossing boundaries, asking questions, and his experience at Beth Tzedec.

What does it take to understand across boundaries? That is, what is required when we want to understand something or someone across distances of location, history, ethnicity, religion, power, gender, and all of the various domains by which we define and are defined by ourselves and others? This is at once a complex and simple question, hiding within it nuances of meaning, layers of significance and a multitude of perspectives. Since everything we know is a product of interpretation, understanding the stranger, as well as those who are nearest and dearest to us – indeed understanding even ourselves – is a complicated business. In what follows I want to suggest that a key to any such understanding lies in the process of educating the imagination, and that curiosity marks the essential beginning of this process. As we shall see, when we engage in the act of understanding anything at all, we practice an imaginative exercise, one which stretches what we know to include that which is strange and unknown.

The study of understanding, also known as the theory of interpretation, is called hermeneutics. Derived from the Greek hermeneia (meaning interpretation/translation), and originally focused on the interpretation of religious texts, hermeneutics now includes the interpretation of all signs, including the written or verbal words of another, or an event, sign or symbol in the world, or indeed the content of our own experience. A key concept in most theories of interpretation is the hermeneutic circle, by which is meant the back-and-forth engagement of the interpreter and the text – and here, the generic term text signifies anything that may bear meaning.

The circle begins when we are first confronted by something that we want to understand, which appears to us as a singular sort of question: What am I? This question, a challenge to our nature as beings capable of knowledge, ushers curiosity onto the stage. Without an initial willingness to allow ourselves to respond to the challenge of the unknown, no understanding is possible.

It is worth noting here that while we may think curiosity is an act of will, generated through our own outward-looking desire to grasp the world, it is in fact summoned by the Other. Curiosity is a response. Without the initiatory bidding of the text, our curiosity would be empty. For if there is no prior question – no initial What am I? – of what could we be curious? In response, we allow ourselves to be brought into engagement with the Other, thus subsuming our own knowledge, and our own will to dominate, name and categorize, to the as-yet-unknown. Curiosity is therefore not only a response but also a sacrifice. We humble ourselves in order to know the Other. This kenosis or self-emptying is essential if we are to make room in our own conceptual scheme(s) for the Other we seek to understand.

In response to the invitation, What am I?, we tentatively guess. In an act of imaginative comparison and generalization, we venture a response that we hope accommodates the text into our frame(s) of reference. Having limited access to the text’s own fundamental sources of meaning, we supply these from our own background: we ‘charitably’ donate our own sense of what the text could possibly be, as well as how it might relate to the world. In so doing we transform the unknown into our best guess as to what it might be, stretching our own categories and concepts. Our attempt to name and categorize the strange text has transformed it into a new form – and with this new form is born yet another challenge: What am I?

And so the wheel turns.

Being faced with the challenge of understanding the new and the strange, we imaginatively see it as something more familiar to us, only to find that our seeing as has revealed – or created – new features hitherto unseen. The circle turns as we venture another interpretation, another transformation, another challenge. Gradually we hone in on the centre of the text, slowly pinning it down, at least for the time being, to what it is for us.

The hermeneutic circle becomes a spiral as we get closer and closer to our interpretation, until the text has taken its place within our conceptual scheme.

As can be seen from the above description, hermeneutics can be tremendously abstract and theoretical. An illustration might be useful here. Imagine you inherit an object from a distant relative. Upon delivery you find that it is a rather large, solid and geometrical construction. Other than that, you are not quite sure what it is. After the movers leave it in the middle of your living room you realize the conundrum you face: what to do with it? Getting rid of it seems both ungrateful and inconvenient, and besides, there is something you like about it … but just what is it? And where are you going to put it? You rearrange your furniture to make room for it, first in one place, then another, searching for the right fit. In one layout you decide that the new thing might make a very useful coffee table, until you see it as a kind of chair within a different scene, and lastly as an objet d’art in yet another design. The inherited object forces you to rearrange your own furniture and thus the overall design of the room. Settling on a place for the new thing/coffee table, you find your living room re-described. Where once you sat in one corner of the room near the fireplace, the new design has you next to a large window, from which you can view the trees in your garden as the dappled sun warms your face and shoulders.

As can be seen from the above description, hermeneutics can be tremendously abstract and theoretical. An illustration might be useful here. Imagine you inherit an object from a distant relative. Upon delivery you find that it is a rather large, solid and geometrical construction. Other than that, you are not quite sure what it is. After the movers leave it in the middle of your living room you realize the conundrum you face: what to do with it? Getting rid of it seems both ungrateful and inconvenient, and besides, there is something you like about it … but just what is it? And where are you going to put it? You rearrange your furniture to make room for it, first in one place, then another, searching for the right fit. In one layout you decide that the new thing might make a very useful coffee table, until you see it as a kind of chair within a different scene, and lastly as an objet d’art in yet another design. The inherited object forces you to rearrange your own furniture and thus the overall design of the room. Settling on a place for the new thing/coffee table, you find your living room re-described. Where once you sat in one corner of the room near the fireplace, the new design has you next to a large window, from which you can view the trees in your garden as the dappled sun warms your face and shoulders.

Curiosity is humbling, sacrificial and transformative. The space it creates in our ordinary conceptual schemes allows room for the imagination to play with new possibilities, rearranging our conceptual furniture and re-describing our forms of life. Being curious, and responding to the call of the Other, bids us to redraw our blueprints of the world in novel ways. Doing so we make room for the Other in our world(s), allowing us to be hospitable – but just as importantly we discover new ways of being ourselves because of the Other. Our imaginations become educated as we survey new and different vistas, and we are transformed in the process.

Curiosity is thus the first, essential step in the process of understanding across boundaries. It ushers in the opportunity to grow and train our imaginations. It is a necessary condition of discovery, but it is by this token also the key element in our transformation into new and perhaps better versions of ourselves.

As the latest Lil Faider Interfaith Scholar-in-Residence at Beth Tzedec, I have been privileged to be a part of a curious community. The congregants at the synagogue have opened their arms and hearts to welcome me into their midst as but one way to express their open minds to understand and be understood by their neighbours. The conversations we have had have been, I daresay, revelatory.

Inter-religious dialogue can sometimes be a familiar re-hashing of tired shibboleths, uttered by people for whom such dialogue is hardly necessary. I am glad to say that this has not been my experience of the Interfaith Scholar-in-Residence program that Lil Faider had the great foresight to endow. The real fruit of inter-religious dialogue is to come to understand how a tried and tested tool we have relied on for a long time can also be used in different ways to accomplish different tasks. Just as figuring out what that strange and ignored tool in our Swiss Army knife is actually for, learning about another tradition reveals new forms of life; that is, re-descriptions of how to become ourselves.

I firmly believe that this model of inter-religious dialogue should be widely emulated. It provides room to think, opportunities for hospitality, and the beginnings of lasting friendships.

Visit Beth Tzedec Congregation’s website to for more information, and to watch video presentations by all the Scholars-in-Residence, including Dr. Tinu Ruparell.