Imagine a spiritual elder giving you this advice:

If the devil tells you something is too fearful to look at, look at it. If he says something is too terrible to hear, hear it. If you think some truth unbearable, bear it.1

It’s a frightfully paradoxical bit of guidance. Who but G.K. Chesterton and his rather shabby but brilliant creation Father Brown would give such a contrary piece of advice?

For those of you who have never seen, read or heard of Father Brown, he is a fictional Roman Catholic priest who solves crimes and mysteries, deliciously served up for 26 years (from 1910 to 1936) in 53 short stories penned by the English writer, poet, philosopher, orator, and late convert to Catholicism, G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936). Father Brown, as Chesterton’s mouthpiece, offers keen insights and lively observations regarding all manner of life happenings.

Though from another age, another style, and an ancient orthodoxy, the priest and his creator have a lot to say to us in our jam-packed days of political chaos and all-pervasive social media.

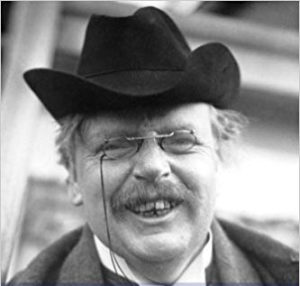

G.K. Chesterton was a unique character who, to the delight of his many fans, was happy to share his unconventional and unworldly wisdom. He was larger than life, 6’4” and almost 300 lbs., a popular debater and firm friend of George Bernard Shaw, as well as Hillaire Belloc and H.G. Wells. Chesterton read over 10,000 books, memorized many parts of them, wrote over 100 books himself, contributed to 200 others, penned several hundred poems, and published over 5000 essays in newspapers and magazines.

Chesterton’s ‘Father Brown’ character was inspired by the Rt. Rev. John O’Connor, a Roman Catholic parish priest who became a good friend, and who was instrumental in Chesterton’s conversion to Catholicism at the age of 46.

For those of us late to discovering the books, there is also the wonderful Father Brown television series on BBC, which began in 2013 and still continues, starring the inimitable Mark Williams. (Episodes can currently also be viewed on Netflix.) In the series, the ungainly, awkward but hugely endearing priest applies his love and knowledge of human nature to ensure that justice is served and the perpetrator is held accountable – and wherever possible, redeemed for eternity.

What may not be always obvious from the TV series, but is eminently declared in the books, is that Father Brown takes a decidedly spiritual and psychological view of criminals and non-criminals alike. He gained his deep understanding of the human – and indeed, criminal – mind from hearing confessions. He is often uncannily successful at predicting their behavior because, as he humbly points out, they are just like him – too often blind to their weaknesses, limitations and mistakes.

Father Brown also understands evil intimately. As he discusses a crime in “The Secret of Flambeau” (1927) he explains, “When I tried to imagine the state of mind in which such a thing would be done, I realized that I might have done it myself under certain mental conditions. And then, of course, I knew who really had done it.”

Father Brown also understands evil intimately. As he discusses a crime in “The Secret of Flambeau” (1927) he explains, “When I tried to imagine the state of mind in which such a thing would be done, I realized that I might have done it myself under certain mental conditions. And then, of course, I knew who really had done it.”

Like Sherlock Holmes (whom Chesterton admired very much), Father Brown doesn’t miss a thing when it comes to observing critical details. But there are many areas where Holmes and Brown part as detectives. Whereas Holmes relies coldly, pretentiously and narrowly on logic to decipher his clues, Brown looks to God for direction, and seeks to understand the motivations of the heart. As author John Peterson, a long-time ‘Chestertonian’ and editor of a volume of selected Father Brown stories, comments, “Though he is a keen observer and sound logician, the real secret of Father Brown’s success is his practical knowledge of human nature and his ability to apply that knowledge to the problem at hand. In “The Duel of Dr. Hirsch” (1914), Father Brown explains to a friend, “I can always grasp moral evidence easier than the other sorts. I go by a man’s eyes and voice, and whether his family seems happy, and by what subjects he chooses to discuss.”

We are lucky indeed that Chesterton should apply his genius to the writing of mysteries, bringing Father Brown to life. Mysteries are, after all, about seeing what is plainly before us, finding those tantalizing truths we so often keep missing. Chesterton was a master at plunging into the deep, with a great sense of humour, a love for paradoxical realities, and a gift for fashioning a ripping good story.

To quote John Peterson again, “Chesterton never found a literary form more agreeable to his genius. This is also a great good fortune for devoted readers of murder mysteries, for such stories have never been presented with anything approaching his complexity and depth.”

Here’s a taste of that complexity and depth. In “The Queer Feet” (1911), the priest-detective is called to the Vernon Hotel, where a waiter is dying. The hotel is hosting the annual dinner of The Twelve True Fishermen Club. A dazzling showcase of bejeweled fish-knives entices Flambeau, the notorious international jewel thief who appears in many of Father Brown’s early adventures. When a crime is committed, Father Brown solves it by listening to and interpreting a set of footsteps, and eventually rescues the enormously valuable cutlery. More importantly, he rescues the thief. Flambeau, he tells the Club members, has repented. The Club’s members are incredulous. Father Brown explains:

If you doubt the penitence as a practical fact, there are your knives and forks, your silver fish. But He has made me a fisher of men.” One of the members asked: “Did you catch this man?” Father Brown responded: “Yes, I caught him, with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world, and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread.

This is just one of the many glimpses of Christian beliefs and attitudes, central to these stories, which Chesterton cleverly imparts. Father Brown sees evil, but he does not judge the evildoer. Where he understands, he offers charity, if not forgiveness – and he always seeks repentance and redemption.

Chesterton’s mission in life seemed focused on shaking up our view of religion, and eliciting a fresh and enlightened, yet decidedly ageless, perspective on eternity.

Chesterton’s mission in life seemed focused on shaking up our view of religion, and eliciting a fresh and enlightened, yet decidedly ageless, perspective on eternity.

In Father Brown, he succeeded magnificently.

All photos in the public domain.

- The Wisdom of Father Brown, by G.K. Chesterton (1911)