Mercury 13

Directors: David Sington, Heather Walsh

Produced by Fine Points Film & Dox Productions

80 minutes

Trailer for Mercury 13 (1:48):

When we are first introduced to the women that participated in the “Mercury 13” space program, we see them as typical older women. They meet in a small, rural coffee shop, as my grandmother often does with her girlfriends, and at first glance might appear to be comparing grandchildren. However, the opening question shared between these women is, “What type of airplane do you usually fly?” The women then engage in shoptalk about different airplane models and engines and their flying preferences now, compared to when they were younger.

Left: Mercury 13 Director David Sington. Right: Gene Nora Jesson, one of the Mercury 13 (many of whom, like her, are still piloting planes)

This type of conversation takes the viewer by surprise, as most of the women in our lives the same age as the Mercury 13 never had the freedom or experience of being airplane pilots. In the late 1950s, when these women were beginning their flying careers, most of their female peers were seemingly tied down – to the Earth and their families, and to the household responsibilities of washing the dishes and tidying the house and tending to the children and the garden and the roast chicken in the oven. The excellent documentary Mercury 13, directed by David Sington and Heather Walsh, explores the women who were invited to escape the housewife scenario by taking the physical and mental tests to become astronauts.

By 1957, with the launch of the Sputnik satellite, NASA was becoming competitive with the Russian space program. In 1958, spurred on by a pre-Cold War fear of falling behind in scientific discovery, the United States began to search for a team of men to participate in America’s first manned space flight program. The “Mercury 13” program was started by NASA’s Chairman of their Life Sciences Committee, Dr. William “Randy” Lovelace II, who believed that women had something important to offer to space travel physically, mentally, and emotionally. Thirteen female pilots from across America were selected by Lovelace to participate in the same physical and psychological testing as the men who were already training to become astronauts. His plan was to compare their test results to those of the men, and prove that they could be an integral part of the spaceflight program.

The interviews with members of the Mercury 13 are woven together with remarkable archival footage from the 1940s, 50s, and 60s of planes on runways and the portrayal of female pilots in the media. An old film special on women pilots in black and white shows the women expertly flying planes, and then landing them to powder their noses and reapply lipstick. These clips truly highlight the beliefs in gender roles at the time these women were flying, and the desperation of the media and society to continue to portray softness and femininity in the women despite their successes in the male-dominated field of flight.

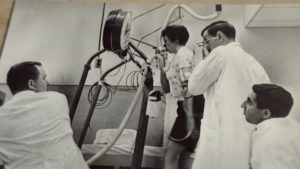

Similarly, the footage of the NASA program as well as the women undergoing the physical and psychological tests provides a beautiful and historical aspect to the film. At one point, archival footage is altered in an imaginative way to exemplify what history might have looked like had women been allowed to be a part of the first space flight; footage of Neil Armstrong dubbed over with a woman’s voice saying, “One small step for woman, one large step for mankind.” The names on banners in “Welcome Home” parades for the astronauts change from “Neil” and “Aldron” to “Sarah” and “Janey”.

One of the most striking themes of the documentary is that all the women share a similar reason behind their love for flight and the idea of space travel. All the women interviewed delight in the feeling of weightlessness and of freedom.

“The freedom, the smell of the exhaust, the air going over my hair,” says a nostalgic Mary “Wally” Funk, “It was me; it was part of me. I had those wings on too.” Her sentiments were echoed by one of her Mercury 13 partners, Sarah Ratley, who says, “It was the thrill of going up and being free up there,” when recalling the joy of flying. Though there were many barriers against the women societally and in their careers as pilots, these problems melted away when they were in control above the clouds, weightless. Once they found this weightlessness and this joy, as Ratley puts it, “a lot of them didn’t want to go back to the kitchen. They wanted their freedom again.”

The motif of weightlessness returns when the women take NASA’s physical and psychological tests, and come back with far better results than expected in the ‘sensory deprivation test’, which involved total submersion in a tank of room temperature water. While the men who completed this test reported to have hated it, the women excelled in the test, and even enjoyed it. “The women were perfectly happy to lay there forever,” says Ann Hart, the daughter of the Mercury 13 member, Jane Hart, “and the men just couldn’t take it. They started crawling out of their skin.” Jerrie Cobb, a member of Mercury 13, even broke a record for the test, staying in the sensory deprivation tank for nine and a half hours. Again, the female pilots were motivated and delighted by a sense of freedom and weightlessness that they found in the tank, perhaps demonstrating the same need for peace that often prompts busy women to escape to their own bathtubs.

Wally Funk today. She now has over 19,000 flight hours, and is excited about the idea of traveling in space someday.

The women of Mercury 13 were ultimately brought “back down to Earth” when their space program was cancelled in favour of male pilots who had fighter pilot training. Women at the time were unable to receive this training, since they were barred from Air Force training schools. Seeing these tenacious women aspiring to achieve something ground-breaking, and paving the way for the first female astronauts several years later, is an inspiring watch for girls, women, and anyone who dreams of reaching for the stars.

Mercury 13 is now showing on Netflix.

Photos courtesy of Netflix.