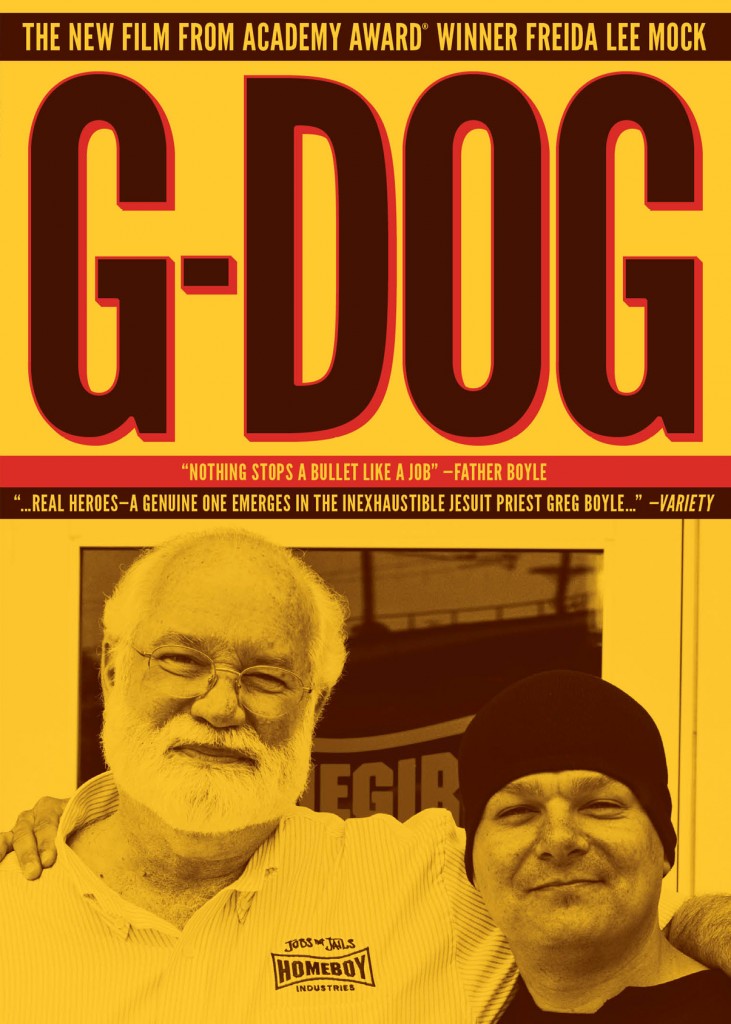

A tough-looking young man looks directly into the camera and says with a crooked grin, “G-Dog is cool, he’s a homeboy, a homey, one of our own.” Who would guess that the canine in question is Father Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest?

A tough-looking young man looks directly into the camera and says with a crooked grin, “G-Dog is cool, he’s a homeboy, a homey, one of our own.” Who would guess that the canine in question is Father Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest?

G-Dog is a touching, fly-on-the-wall documentary about a year in the life of Homeboy Industries, a social enterprise created by Fr. Greg, a.k.a. G-Dog. Directed by Academy Award winning filmmaker Freida Lee Mock, this is the story of a visionary who launched the most successful gang intervention program in America. It’s not without irony or sadness, as we come to see – because it’s also a story of survival.

The documentary takes us right into the day-to-day life of Homeboy Industries. We are privy to uncomfortable details about disappointment and frustration and failure, but we also are shown an intimate view of the people dedicated to this hardest of missions.

There’s a lot of buzz nowadays about social enterprise, and Homeboy Industries is a shining example. Former gang-involved men and women make meals in the industrial kitchen, serve food in the café, look after children in the daycare, and design silkscreen t-shirts in a back room. But not many social enterprises have the soulfulness that Fr. Greg inspires. It’s a home, where kids who feel abandoned and hopeless, who have no one but fellow gang members to hang out with, find a place where they are accepted, loved and given a second chance at life.

The subjects do not seem to be aware of the cameras hovering over and around them. Too often, a video about a mission organization is like a one-hour commercial where everything is staged. Not this time. That said, Fr. Greg seems to be always calm and on his game, speaking from his heart as he manages extremely difficult situations and people. In fact, he seems to thrive on crisis – and in the last half of the film Homeboy Industries is facing a huge crisis that could destroy it. That’s when the film soars. We have a sense that no one, not even the filmmakers, know what is coming around the corner. But we also get the sense that the Holy Spirit is kicking into gear.

For me, the most beautiful aspects of the film are the intimate portraits of gang members who have come under the wing of Homeboy Industries and Fr. Greg. These are young men and women whom the police, social workers and judges have given up on. You can tell that for many of them, Fr. Greg is the father they never knew. We hear their pain, and we see their joy.

How did Greg Boyle, who grew up in a white, middle-class suburban family, come to be here? After he became interested in religious life, went to seminary and joined the Jesuits, he worked in the slums of Bolivia and met the poor for the first time. His calling to live with the underprivileged became clearer in the 1970s when he moved back to Los Angeles.

Fr. Greg became a priest in one of the most dangerous Catholic parishes in the U. S., where the police told him to stay indoors if he wanted to stay alive. Violent gangs were a common feature of the neighbourhood, with police helicopters surveying the streets every night of the week. Gang membership here began as early as age 12, with rival gang members barely out of elementary school killing each other.

Instead of giving up or fighting back, Fr. Greg took the third way, a positive alternative, trying to address the root causes of poverty and alienation. Fr. Greg organized his parishioners and together they appealed to local employers to hire these troubled kids in their neighborhood. They created jobs painting over graffiti and cleaning up garbage. They made sure the kids stayed in school. Many people thought this idealistic young man with a Roman collar was a renegade, but before long crime rates in the neighbourhood started to come down and Fr. Greg turned his opponents into fans.

G-Dog is a challenge to followers of G-sus. We all know there are poor, disenfranchised and dangerous people in our cities. But so rarely do we follow the challenging highway of mercy that G-Dog travels. The film asks all of us if there is a dark place where we have been called to shed light, to create family.

To quote Fr. Greg, the measure of your compassion is not your service to those on the margins, but your willingness to see yourself in kinship alongside them.