On September 17, in the calendar of the church, we remember Hildegard of Bingen, born over 900 years ago in the year 1098. For most of her 80+ years, she lived in an obscure hilltop monastery in the Rhineland of Germany. As a child she was drawn to the religious life, a life of silence and prayer; however a convent could also then be a place of freedom for a woman to develop her intellectual gifts and creativity and care, and she did it all. At age 38 she became abbess of her community, and she would eventually build a second convent. Her character absolutely teemed with creativity, and yet she could also be steely, determined, and, at times, overbearing. Her sisters flourished under her rather unorthodox regime.

The ruins of the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg, Germany, where Hildegard was sent to live as a young teen. Photo by Lisa van Beergen.

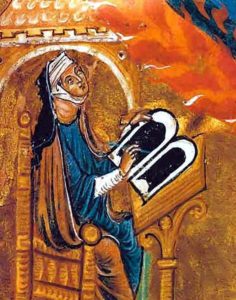

From childhood, Hildegard experienced dazzling spiritual visions. At age 43, an inner voice directed her to tell what she saw. She wrote, “Heaven was opened and a fiery light of exceeding brilliance came and permeated my whole brain, and inflamed my whole heart, and my whole breast.” This began an outpouring of her amazingly original writings and unusual, sometimes-exotic and erotic artistic illuminations. She oftentimes used feminine imagery for God and God’s creative activity. Take, for example, Hildegard’s inspiration from the “Song of Songs” (in the Hebrew scriptures), as she describes the Virgin Mary: “Your flesh has known delight; like the grassland touched by dew and immersed in its freshness: so it was with you, O mother of all joy.”1

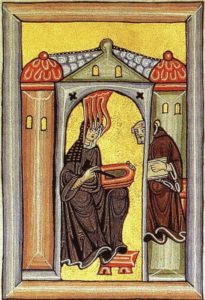

Frontispiece of Scivias, showing Hildegard receiving a vision, dictating, and sketching on a wax tablet. Scivias is an illustrated work by Hildegard, the title coming from the Latin phrase “Sci vias Domini”(“Know the Ways of the Lord”). Scivias was completed in 1152, describing 26 religious visions Hildegard experienced, the first of three works she wrote describing her visions.

In 1147, her friend, the Cistercian Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, recommended Hildegard’s first book of visions to the Pope, who authenticated the revelations. There is an old aphorism that “some people are so heavenly minded, they are of no earthly good.” But that is not Hildegard. She had a liminal awareness: very grounded in the here-and-now, and yet soaring with the radiant glory of God. Because she was as spiritually perceptive as she was politically savvy, she was eagerly sought for counsel and encouragement by the royalty, by abbots and abbesses, by prelates and paupers and so many in between.

Hildegard carried out four preaching missions in northern Europe, an unprecedented activity for a woman in that time. She practiced medicine, focusing especially on women’s needs. She published treatises on natural science and philosophy, wrote liturgical drama, and composed music. For Hildegard, music was essential to worship. Her musical compositions were unusual in structure and tonality, rather evanescent, mesmerizing, and enchanting. If you have heard any of her music, you will know this. Hildegard had grown up hearing the chants of the Roman Mass; now she set her own vibrant, colorful verses to music to create antiphons, sequences, and hymns. Her hymnody and poetry abounds in colorful images of natural, organic things: gardens, fecundity, flowers, jewels.2 She said of herself, “I am like a feather on the breath of God.”

Several themes prevail in Hildegard’s writings, which make her witness so poignant and precious to us today:3

- The stewardship of creation and holistic living. Hildegard revered the earth as a place of wonder, a region of delight and glory to God, and entrusted to us to be cherished, enjoyed, and protected. She reflected on the life principle of energy shining forth in all living things: people, plants, and everything in between. She originated the word “viriditas,” or “greenness,” to speak of this principle of God’s vitality in all of creation.

- Living a life of compassion and justice-making. Being a contemplative is not an escape from earthly life. Being a contemplative requires a studied awareness of the times, and the need for God’s wisdom in our choice of actions. We’re to be contemplatives in action. Hildegard has recurring themes on social justice: about freeing the downtrodden, about the duty to see that every human being, made in the image of God, has the opportunity to develop and realize their dignity and creativity. Hildegard prayed: “O eternal God, turn us into the arms and hands, the legs and feet of your beloved Son, Jesus.”

- Making a holistic use of our intelligence, intuition, and imagination. We are God’s co-creators. All of life teems with God’s presence and creativity. Hildegard said, “God made [us] mirrors of all heaven’s graces.” We should use all God’s gifts entrusted to us. God’s gifts are to be shared, not squandered, and not denied.

- We have been created in light. That we mirror God’s presence – God’s light! – is a recurring theme for Hildegard. God’s light shines throughout the cosmos and throughout ourselves. Hildegard preached Jesus’ words, “I am the light of the world; anyone who follows me will not be walking in the dark but will have the light of life.”4 And – no surprise – her theology is expansive. She taught that anything that shows us the way to God is “light.”

Hildegard was a complex person, both an inspiration and a challenge to live with. We also know that Hildegard somehow suffered physically, or mentally, or both. Hildegard said, quite autobiographically: “God dwells in bodies that are not whole.” Modern-day commentators, including the clinical neurologist Oliver Sacks, have suggested that she probably suffered from migraines from an early age.5 Whatever her suffering, it makes her prayers for healing and wholeness so personal for her, and so helpful and hopeful for us.6

Here is Hildegard’s antiphon to the Holy Spirit:

The Holy Spirit is a life that gives life,

moving all things.

The Holy Spirit is the root in every creature

and purifies all things,

wiping away sins,

anointing wounds.

The Holy Spirit is radiant life, worthy of praise,

awakening and enlivening

all things.

Blessed Hildegard of Bingen, whom we remember with thanksgiving.

——

- Hildegard of Bingen, in “Ave, Generosa.”

- For Hildegard’s biography, I have liberally drawn from Holy Women, Holy Men (Church Publishing, 2010), pp. 588-589; and from ClassicFm.com: “Hildegard of Bingen: life and music of the great female composer.”

- Praying with Hildegard of Bingen, by Gloria Durka (Saint Mary’s Press, 1991); pp. 25-27.

- John 8:12

- Oliver Sacks (1933-2015), Professor of Clinical Neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, was the author of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Migraine, and various other books. Professor Sacks maintained that this affliction did not call into question whether Hildegard’s visions were authentic insights into the nature of God and God’s relation to the universe.

- “Making Modern Migraine Medieval: Hildegard of Bingen and the Life of a Retrospective Diagnosis,” by Katherine Foxhall in The Cambridge Journal of Medicine; Med Hist. 2014 Jul; 58(3): pp. 354–374.