I was honored when MIT Technology Review invited me to be the first guest curator of its 10 Breakthrough Technologies. Narrowing down the list was difficult. I wanted to choose things that not only will create headlines in 2019 but captured this moment in technological history—which got me thinking about how innovation has evolved over time.

My mind went to—of all things—the plow. Plows are an excellent embodiment of the history of innovation. Humans have been using them since 4000 BCE, when Mesopotamian farmers aerated soil with sharpened sticks. We’ve been slowly tinkering with and improving them ever since, and today’s plows are technological marvels.

But what exactly is the purpose of a plow? It’s a tool that creates more: more seeds planted, more crops harvested, more food to go around. In places where nutrition is hard to come by, it’s no exaggeration to say that a plow gives people more years of life. The plow—like many technologies, both ancient and modern—is about creating more of something and doing it more efficiently, so that more people can benefit.

Contrast that with lab-grown meat, one of the innovations I picked for this year’s 10 Breakthrough Technologies list. Growing animal protein in a lab isn’t about feeding more people. There’s enough livestock to feed the world already, even as demand for meat goes up. Next-generation protein isn’t about creating more—it’s about making meat better. It lets us provide for a growing and wealthier world without contributing to deforestation or emitting methane. It also allows us to enjoy hamburgers without killing any animals.

Put another way, the plow improves our quantity of life, and lab-grown meat improves our quality of life. For most of human history, we’ve put most of our innovative capacity into the former. And our efforts have paid off: worldwide life expectancy rose from 34 years in 1913 to 60 in 1973 and has reached 71 today.

Because we’re living longer, our focus is starting to shift toward well-being. This transformation is happening slowly. If you divide scientific breakthroughs into these two categories—things that improve quantity of life and things that improve quality of life—the 2009 list looks not so different from this year’s. Like most forms of progress, the change is so gradual that it’s hard to perceive. It’s a matter of decades, not years—and I believe we’re only at the midpoint of the transition.

To be clear, I don’t think humanity will stop trying to extend life spans anytime soon. We’re still far from a world where everyone everywhere lives to old age in perfect health, and it’s going to take a lot of innovation to get us there. Plus, “quantity of life” and “quality of life” are not mutually exclusive. A malaria vaccine would both save lives and make life better for children who might otherwise have been left with developmental delays from the disease.

We’ve reached a point where we’re tackling both ideas at once, and that’s what makes this moment in history so interesting. If I had to predict what this list will look like a few years from now, I’d bet technologies that alleviate chronic disease will be a big theme. This won’t just include new drugs (although I would love to see new treatments for diseases like Alzheimer’s on the list). The innovations might look like a mechanical glove that helps a person with arthritis maintain flexibility, or an app that connects people experiencing major depressive episodes with the help they need.

If we could look even further out—let’s say the list 20 years from now—I would hope to see technologies that center almost entirely on well-being. I think the brilliant minds of the future will focus on more metaphysical questions: How do we make people happier? How do we create meaningful connections? How do we help everyone live a fulfilling life?

I would love to see these questions shape the 2039 list, because it would mean that we’ve successfully fought back disease (and dealt with climate change). I can’t imagine a greater sign of progress than that. For now, though, the innovations driving change are a mix of things that extend life and things that make it better. My picks reflect both. Each one gives me a different reason to be optimistic for the future, and I hope they inspire you, too.

My selections include amazing new tools that will one day save lives, from simple blood tests that predict premature birth to toilets that destroy deadly pathogens. I’m equally excited by how other technologies on the list will improve our lives. Wearable health monitors like the wrist-based ECG will warn heart patients of impending problems, while others let diabetics not only track glucose levels but manage their disease. Advanced nuclear reactors could provide carbon-free, safe, secure energy to the world.

One of my choices even offers us a peek at a future where society’s primary goal is personal fulfillment. Among many other applications, AI-driven personal agents might one day make your e-mail in-box more manageable—something that sounds trivial until you consider what possibilities open up when you have more free time.

The 30 minutes you used to spend reading e-mail could be spent doing other things. I know some people would use that time to get more work done—but I hope most would use it for pursuits like connecting with a friend over coffee, helping your child with homework, or even volunteering in your community.

That, I think, is a future worth working toward.

Robot dexterity

Robots are teaching themselves to handle the physical world.

For all the talk about machines taking jobs, industrial robots are still clumsy and inflexible. A robot can repeatedly pick up a component on an assembly line with amazing precision and without ever getting bored—but move the object half an inch, or replace it with something slightly different, and the machine will fumble ineptly or paw at thin air.

But while a robot can’t yet be programmed to figure out how to grasp any object just by looking at it, as people do, it can now learn to manipulate the object on its own through virtual trial and error.

One such project is Dactyl, a robot that taught itself to flip a toy building block in its fingers. Dactyl, which comes from the San Francisco nonprofit OpenAI, consists of an off-the-shelf robot hand surrounded by an array of lights and cameras. Using what’s known as reinforcement learning, neural-network software learns how to grasp and turn the block within a simulated environment before the hand tries it out for real. The software experiments, randomly at first, strengthening connections within the network over time as it gets closer to its goal.

It usually isn’t possible to transfer that type of virtual practice to the real world, because things like friction or the varied properties of different materials are so difficult to simulate. The OpenAI team got around this by adding randomness to the virtual training, giving the robot a proxy for the messiness of reality.

We’ll need further breakthroughs for robots to master the advanced dexterity needed in a real warehouse or factory. But if researchers can reliably employ this kind of learning, robots might eventually assemble our gadgets, load our dishwashers, and even help Grandma out of bed.

—Will Knight

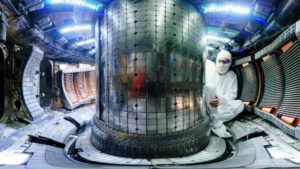

New-wave nuclear power

Advanced fusion and fission reactors are edging closer to reality.

New nuclear designs that have gained momentum in the past year are promising to make this power source safer and cheaper. Among them are generation IV fission reactors, an evolution of traditional designs; small modular reactors; and fusion reactors, a technology that has seemed eternally just out of reach. Developers of generation IV fission designs, such as Canada’s Terrestrial Energy and Washington-based TerraPower, have entered into R&D partnerships with utilities, aiming for grid supply (somewhat optimistically, maybe) by the 2020s.

Small modular reactors typically produce in the tens of megawatts of power (for comparison, a traditional nuclear reactor produces around 1,000 MW). Companies like Oregon’s NuScale say the miniaturized reactors can save money and reduce environmental and financial risks.

There has even been progress on fusion. Though no one expects delivery before 2030, companies like General Fusion and Commonwealth Fusion Systems, an MIT spinout, are making some headway. Many consider fusion a pipe dream, but because the reactors can’t melt down and don’t create long-lived, high-level waste, it should face much less public resistance than conventional nuclear.

—Leigh Phillips

Predicting preemies

A simple blood test can predict if a pregnant woman is at risk of giving birth prematurely.

Our genetic material lives mostly inside our cells. But small amounts of “cell-free” DNA and RNA also float in our blood, often released by dying cells. In pregnant women, that cell-free material is an alphabet soup of nucleic acids from the fetus, the placenta, and the mother.

Stephen Quake, a bioengineer at Stanford, has found a way to use that to tackle one of medicine’s most intractable problems: the roughly one in 10 babies born prematurely.

Free-floating DNA and RNA can yield information that previously required invasive ways of grabbing cells, such as taking a biopsy of a tumour or puncturing a pregnant woman’s belly to perform an amniocentesis. What’s changed is that it’s now easier to detect and sequence the small amounts of cell-free genetic material in the blood. In the last few years, researchers have begun developing blood tests for cancer (by spotting the telltale DNA from tumour cells).

The tests for these conditions rely on looking for genetic mutations in the DNA. RNA, on the other hand, is the molecule that regulates gene expression—how much of a protein is produced from a gene. By sequencing the free-floating RNA in the mother’s blood, Quake can spot fluctuations in the expression of seven genes that he singles out as associated with preterm birth. That lets him identify women likely to deliver too early. Once alerted, doctors can take measures to stave off an early birth and give the child a better chance of survival.

The technology behind the blood test, Quake says, is quick, easy, and less than $10 a measurement. He and his collaborators have launched a startup, Akna Dx, to commercialize it.

—Bonnie Rochman

Gut probe in a pill

A small, swallowable device captures detailed images of the gut without anesthesia, even in infants and children.

Environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) may be one of the costliest diseases you’ve never heard of. Marked by inflamed intestines that are leaky and absorb nutrients poorly, it’s widespread in poor countries and is one reason why many people there are malnourished, have developmental delays, and never reach a normal height. No one knows exactly what causes EED and how it could be prevented or treated.

Practical screening to detect it would help medical workers know when to intervene and how. Therapies are already available for infants, but diagnosing and studying illnesses in the guts of such young children often requires anesthetizing them and inserting a tube called an endoscope down the throat. It’s expensive, uncomfortable, and not practical in areas of the world where EED is prevalent.

So Guillermo Tearney, a pathologist and engineer at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, is developing small devices that can be used to inspect the gut for signs of EED and even obtain tissue biopsies. Unlike endoscopes, they are simple to use at a primary care visit.

Tearney’s swallowable capsules contain miniature microscopes. They’re attached to a flexible string-like tether that provides power and light while sending images to a briefcase-like console with a monitor. This lets the health-care worker pause the capsule at points of interest and pull it out when finished, allowing it to be sterilized and reused. (Though it sounds gag-inducing, Tearney’s team has developed a technique that they say doesn’t cause discomfort.) It can also carry technologies that image the entire surface of the digestive tract at the resolution of a single cell or capture three-dimensional cross-sections a couple of millimetres deep.

The technology has several applications; at MGH it’s being used to screen for Barrett’s esophagus, a precursor of esophageal cancer. For EED, Tearney’s team has developed an even smaller version for use in infants who can’t swallow a pill. It’s been tested on adolescents in Pakistan, where EED is prevalent, and infant testing is planned for 2019.

The little probe will help researchers answer questions about EED’s development—such as which cells it affects and whether bacteria are involved—and evaluate interventions and potential treatments.

—Courtney Humphries

Custom cancer vaccines

The treatment incites the body’s natural defences to destroy only cancer cells by identifying mutations unique to each tumour

Scientists are on the cusp of commercializing the first personalized cancer vaccine. If it works as hoped, the vaccine, which triggers a person’s immune system to identify a tumour by its unique mutations, could effectively shut down many types of cancers.

By using the body’s natural defences to selectively destroy only tumour cells, the vaccine, unlike conventional chemotherapies, limits damage to healthy cells. The attacking immune cells could also be vigilant in spotting any stray cancer cells after the initial treatment.

The possibility of such vaccines began to take shape in 2008, five years after the Human Genome Project was completed when geneticists published the first sequence of a cancerous tumour cell.

Soon after, investigators began to compare the DNA of tumour cells with that of healthy cells—and other tumour cells. These studies confirmed that all cancer cells contain hundreds if not thousands of specific mutations, most of which are unique to each tumour.

A few years later, a German startup called BioNTech provided compelling evidence that a vaccine containing copies of these mutations could catalyze the body’s immune system to produce T cells primed to seek out, attack, and destroy all cancer cells harbouring them.

In December 2017, BioNTech began a large test of the vaccine in cancer patients, in collaboration with the biotech giant Genentech. The ongoing trial is targeting at least 10 solid cancers and aims to enroll upwards of 560 patients at sites around the globe.

The two companies are designing new manufacturing techniques to produce thousands of personally customized vaccines cheaply and quickly. That will be tricky because creating the vaccine involves performing a biopsy on the patient’s tumour, sequencing and analyzing its DNA, and rushing that information to the production site. Once produced, the vaccine needs to be promptly delivered to the hospital; delays could be deadly.

—Adam Piore

The cow-free burger

Both lab-grown and plant-based alternatives approximate the taste and nutritional value of real meat without environmental devastation.

The UN expects the world to have 9.8 billion people by 2050. And those people are getting richer. Neither trend bodes well for climate change—, especially because as people escape poverty, they tend to eat more meat.

By that date, according to the predictions, humans will consume 70% more meat than they did in 2005. And it turns out that raising animals for human consumption is among the worst things we do to the environment.

Depending on the animal, producing a pound of meat protein with Western industrialized methods requires 4 to 25 times more water, 6 to 17 times more land, and 6 to 20 times more fossil fuels than producing a pound of plant protein.

The problem is that people aren’t likely to stop eating meat anytime soon. This means lab-grown and plant-based alternatives might be the best way to limit the destruction.

Making lab-grown meat involves extracting muscle tissue from animals and growing it in bioreactors. The end product looks much like what you’d get from an animal, although researchers are still working on the taste. Researchers at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, who are working to produce lab-grown meat at scale, believe they’ll have a lab-grown burger available by next year. One drawback of lab-grown meat is that the environmental benefits are still sketchy at best—a recent World Economic Forum report says the emissions from lab-grown meat would be only around 7% less than emissions from beef production.

The better environmental case can be made for plant-based meats from companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, which use pea proteins, soy, wheat, potatoes, and plant oils to mimic the texture and taste of animal meat.

Beyond Meat has a new 26,000-square-foot (2,400-square-meter) plant in California and has already sold upwards of 25 million burgers from 30,000 stores and restaurants. According to an analysis by the Center for Sustainable Systems at the University of Michigan, a Beyond Meat patty would probably generate 90% less in greenhouse-gas emissions than a conventional burger made from a cow.

—Markkus Rovito