Recently I attended an event in Toronto themed, “Young Rabbis Speak: Where are your Jewish Boundaries?” The event involved a panel of four rabbis from different denominations addressing such ethical controversies as the use of technology on the Sabbath, same-sex attraction, and interfaith marriage. The event was promoted as an opportunity to explore questions such as “Who is in and who is out?” and “How do we relate to contemporary hot button issues?”

This event then led me to the Jewish literature section of a bookstore where one particular book attracted my attention, Chaim Potok’s novel, My Name is Asher Lev (New York: Fawcett Crest, 1972). Asher comes from a Hasidic family. His father does important work for the Rebbe. Young Asher is supposedly devoted to studying the Torah. He measures time during his childhood “by the holidays and festivals, by the events in the lives of the people around me. Rosh Hashonoh, Yom Kippur, Succos, Simchas Torah, Hannukah, Purim…” But Asher is different from his family because his prodigious artistic talent often involves exploring a tradition foreign to and, in many cases, perceived as opposed to his Jewish faith. Asher experiences the tension between religious piety and artistic imagination. As he grows up, he continues to practice Jewish deeds and yet he also learns to sketch nudes and crucifixions, which is against the Torah and is dividing his family. His secular Jewish art teacher and mentor, Jacob Khan, insists that Asher must understand what a crucifixion is in art if he would like to become a great artist. “The crucifixion must be available to you as a form,” insists Khan.

This beautiful, sorrowful, and anguish-filled paragraph expresses the crux of the drama:

“I painted swiftly in a strange nervous frenzy of energy. For all the pain you suffered, my mama. For all the torment of your past and future years, mama. For all the anguish this picture of pain will cause you. For the unspeakable mystery that brings good fathers and sons into the world and lets a mother watch them tear at each other’s throats. For the Master of the Universe, whose suffering world I do not comprehend. For dreams of horror, for nights of waiting, for memories of death, for the love I have for you, for all the things I should remember but have forgotten, for all these I created this painting – an observant Jew working on a crucifixion because there was no aesthetic mold in his own religious tradition into which he could pour a painting of ultimate anguish and torment.” (pg. 313)

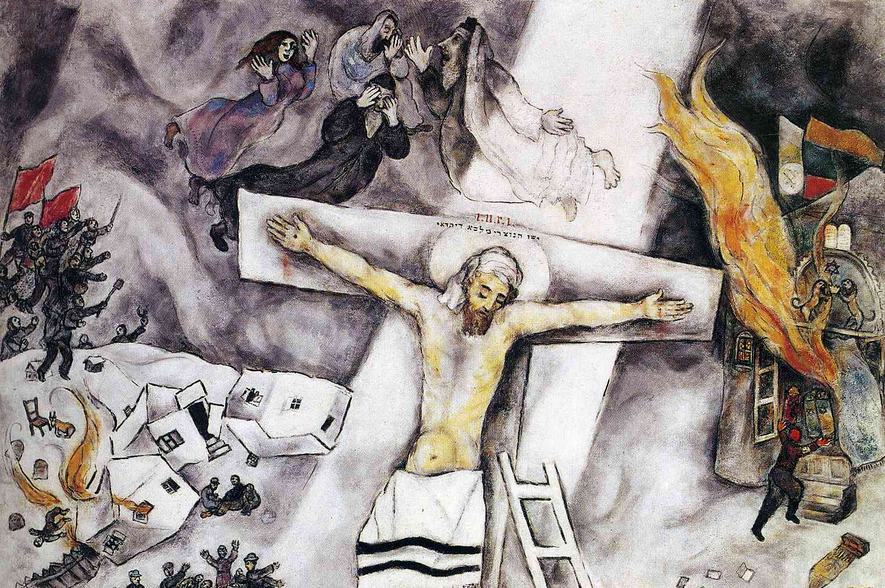

Asher Lev is a fictional character but he has a historical counterpart, artist Marc Chagall. This summer, I finished reading Potok’s novel just before visiting the Art Institute of Chicago. I was delighted to discover so many works of Chagall there. And to my surprise, I came upon Chagall’s profound painting called White Crucifixion. I was in awe of this painting in which Jesus is on the cross in the midst of the Holocaust – the ashen colours, floating bodies, tumbling and flaming houses, a mother shielding her child, Jewish men fleeing and scrambling as they carry Torah scrolls, the inscription on the cross written in Hebrew.

Most amazing was that I was beholding artwork by Asher Lev’s nonfiction alter ego. Marc Chagall was also a Jew raised in a Hasidic environment. Looking at Chagall’s painting, I returned imaginatively to the memory of Asher’s parents’ response to seeing, unveiled to their total shock and surprise, Asher’s two Brooklyn Crucifixion paintings at a New York art show. What must his parents have thought? What would it be like for them, confronted by such a painting at once idolatrous and yet, there, before them, in a real and meaningful way? As Asher said, he painted it because there was “no aesthetic mold in his own religious tradition” to depict the anguish Asher’s art brought to his relationship with his parents, most especially with his father.

Many Jews find Potok’s novels obnoxious. Pope Francis has reportedly said that Chagall’s White Crucifixion is his favourite painting. What are we to make of this? Some would say that artists and philosophers should not be such troublemakers. It can certainly be a lonely and isolating life. And yet, besides their great works of art, there is something that makes characters such as Asher Lev and Marc Chagall true heroes: they practice courage by responding to the call to express their art even when doing so is at odds with convention, and misunderstood by others. As Asher says, “Some art is difficult because life is difficult.” Chagall certainly affirms the difficulty of life and yet he also says, “In the arts, as in life, everything is possible provided it is based on love.” What makes the lives of great artists true works of art is their ability to hold together love and difficulty, and a thousand other paradoxes.

Pingback: Jews, Crucifixions, and Loving the Difficult | John Paul II Philosophical Studies