My mother, Helen Goertzen, was a loving, caring nurse for most of her life, looking after my father who had a heart condition and died far too soon. Upon her retirement and the loss of my Dad, she slowly descended into a paranoid form of dementia. I helped care for her for over 20 years.

My mother, Helen Goertzen, was a loving, caring nurse for most of her life, looking after my father who had a heart condition and died far too soon. Upon her retirement and the loss of my Dad, she slowly descended into a paranoid form of dementia. I helped care for her for over 20 years.

Like many people in my position, I found it difficult to explain my feelings to others. Mom could be sitting right beside me, yet I missed her terribly. Then there’s the guilt about feeling shackled to this person, even though you love them. Life seems to be passing you by.

My mother passed away suddenly in 2012 from heart failure. Her last emergency day in the hospital was not pleasant, as her form of dementia often included acute fear. She had been brought in for tests after a fainting spell. She was very frightened, and when we wanted to take her back to the care home, she literally fought us like a desperate child, thinking the ambulance attendants wanted to kill her. She died the next day.

Some time later, the time came to clean out some files in my studio, and I came upon a reminder of her suffering – little notes that she had written in her confused state of mind while still living on her own. I had gathered them up and put them in a file when we moved her from her apartment into the care home. Mom often misplaced personal items, and unable to admit her forgetfulness, her mind made up stories about other people intruding into her sanctuary. When paranoia takes root, reason decreases, and imagination increases dramatically.

She told me about the people who insinuated themselves into her home to eat her food, steal small items and move things around – even rearranging her drawers, cupboards and purse. At the worst stages, she imagined that these folks had moved into the apartment above her, coming down to her kitchen for breakfast.

Sometimes, “those people” brought their children along with them, allowing the children to scratch her piano bench, pick the leaves off her floral arrangements, and cut the edges of doilies. She insisted that a man used a rope and harness to climb onto her balcony at night, and then sit in her living room and listen to her radio.

The notes I had tucked away in my filing cabinet were addressed to these “visitors”, or “destroyers” as she sometimes called them. She told them she couldn’t afford to feed them, and that they should “get a job!”

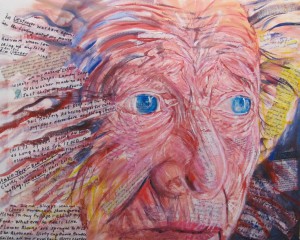

I knew that I needed to do something with all these little notes. Throwing them away seemed like a disregard for her distress, so I decided to work them into a painting about dementia. I would attempt to put myself into her world and try to understand what she had felt.

I found a photo that I had taken of her in her favourite restaurant, shortly before her passing, and sketched the face on the canvas.

What is it like to live in constant fear – where one’s imagination goes wild, and everyone is “looking at you” and judging you? My hands shook and I started to weep as I tore the edges from all of the notes and made them into smaller pieces to attach to the canvas.

During the journey of helping and caring for my Mom, I had become a widow, and was dealing with desperate feelings of my own. My mother was immersed in her helpless little world, unable to comfort me. This brought on self-condemnation for wanting a mother back, to console me. I was angry that I had to be the parent and not the child. Fortunately, with the love and support of family, friends and church network, I received much prayer and support to help wade through the muck of my grief and loss.

During the journey of helping and caring for my Mom, I had become a widow, and was dealing with desperate feelings of my own. My mother was immersed in her helpless little world, unable to comfort me. This brought on self-condemnation for wanting a mother back, to console me. I was angry that I had to be the parent and not the child. Fortunately, with the love and support of family, friends and church network, I received much prayer and support to help wade through the muck of my grief and loss.

While creating this painting, I studied the face of my Mom, noticing every wrinkle, shadow and highlight as an insight into what she was feeling at the time. Every stroke of the brush seemed to ease and release – something.

I can never hope to fully understand her anxiety and desperation, but somehow it felt good to make use of those nasty little notes that had been taking up space in my files. They are now in a place of reminder that we need to show a bit more patience and love to those living in the prison of their anxieties.

To quote Bette Davis, “growing old ain’t for sissies…”