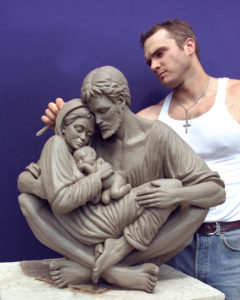

Internationally acclaimed Canadian artist Timothy Schmalz has been sculpting for over 25 years. He is known around the world for his large public monuments in bronze as well as hundreds of commissioned works for Christian churches in traditional figurative style. His work is deeply influenced by the great artists of the Renaissance and by his Christian faith, as he creates new forms and representations.

Internationally acclaimed Canadian artist Timothy Schmalz has been sculpting for over 25 years. He is known around the world for his large public monuments in bronze as well as hundreds of commissioned works for Christian churches in traditional figurative style. His work is deeply influenced by the great artists of the Renaissance and by his Christian faith, as he creates new forms and representations.

Schmalz was commissioned to create a two-metre-by-two-metre bronze memorial by the Fort McMurray Fire Department just weeks before the recent wildfire. What started as a project to commemorate the contributions of Fort McMurray’s firefighters has taken on new meaning, and is now a symbol of their heroic efforts to save the city. It is scheduled to be installed in Fort McMurray in September.

One of Schmalz’s other life-size bronze works that has recently garnered plenty of attention is called Homeless Jesus. It depicts Jesus as a homeless person lying on a park bench, the wounds of crucifixion visible on his feet. First installed at the University of Toronto’s Regis College, casts of the sculpture are now in almost 40 locations around the world, including the Vatican. The sculpture is controversial, and has been criticized and rejected in a number of locations. Pope Francis blessed the artwork in 2013, calling it a “beautiful and excellent representation of Jesus.”

One of Schmalz’s other life-size bronze works that has recently garnered plenty of attention is called Homeless Jesus. It depicts Jesus as a homeless person lying on a park bench, the wounds of crucifixion visible on his feet. First installed at the University of Toronto’s Regis College, casts of the sculpture are now in almost 40 locations around the world, including the Vatican. The sculpture is controversial, and has been criticized and rejected in a number of locations. Pope Francis blessed the artwork in 2013, calling it a “beautiful and excellent representation of Jesus.”

Audio Highlights from Interview:

Kolbe Times: Tell us about your childhood and spiritual background.

Timothy Schmalz: I grew up in Elmira, Ontario, which is a very small town. I was, in a sense, a very materialistic child, in that I wanted to possess things. I found an outlet for that in creating. I discovered that I could draw or sculpt these unattainable objects, these toys that I wanted, and I was satisfied that they didn’t have to look perfect. I think many artists at an early age invent the things they want to have. I’ve always thought that visual art is very physical; you’re creating things that take up space. Your creations are alive, in a sense – especially with sculpture.

I would describe my parents as secular humanists. I was baptized as a Catholic, but it would be an overstatement to say there was an emphasis on Catholicism in my family. Most of the time I was left up to myself as far as ideas about spirituality goes – a “free-range” child, in a sense. I really do think that was very positive for me, because when I did have a conversion experience when I was 17 or 18 years old, I looked at Christianity with fresh but mature eyes, and found it absolutely fascinating. I think I escaped what some Catholics experience, which is that their religion was taken as some sort of punishment – you know: “You’re going to have to go to church!” “No, no!”

For me, it was a mysterious world that seemed all new to me. When I started learning about the saints, and reading works like the Confessions of St. Augustine, it was, like, so fascinating, so amazing! So I think it was beneficial for me, as far as my creativity is concerned. Even now, when I create a sculpture, I do my best to look at a concept with a fresh perspective. I think that‘s how you can come up with creative ways of celebrating the Creator.

When I was 18, I went to the Ontario College of Art and Design. At that point I stayed in Toronto and had a studio there for about 5 years. Then I moved back into the country.

Kolbe Times: What sparked your conversion when you were a teenager?

Timothy Schmalz: I was in a state of desperation at about age 17, and at that time I became a Christian. But a few years later, I kind of had an artistic conversion. I found myself in the same lost state with my artwork at the age of 19 that I experienced with my personhood at the age of 17. It came to a head when I rejected and turned away from what I would now consider the very nihilistic artwork that I was doing in my early teens, and that I was encouraged to make in Art School, mimicking Jackson Pollock and Picasso and other artists like that.

It’s interesting, because it was by looking at the great Masters from the Renaissance – my favourite sculptors have always been Christian sculptors – that I started to understand that in order to do a great piece of artwork, you need great subject matter. I felt that there wasn’t enough substance in what I was producing in my Art School classes, and I turned to the artwork that I appreciated.

It’s interesting, because it was by looking at the great Masters from the Renaissance – my favourite sculptors have always been Christian sculptors – that I started to understand that in order to do a great piece of artwork, you need great subject matter. I felt that there wasn’t enough substance in what I was producing in my Art School classes, and I turned to the artwork that I appreciated.

So I found myself down in the basement at Art School a lot. It was my way of disagreeing with the teachers about the premise of artwork. Eventually I built my own studio – in a sense, I got my own school started and started teaching myself, which is still happening right now. I feel that I’m still learning quite a bit, after 25 years of obsessively doing sculpture.

One thing that I still find fascinating about Christian sculpture is the period of the Reformation, when many, many sculptures were destroyed. They actually destroyed sculptures more often than paintings. Somehow a painting was okay, but a sculpture was dangerous. It made me think about the power of 3-dimensional sculpture, and how that’s evident during that period of our Christian history.

Kolbe Times: And many people would say that power is definitely evident in your artwork.

Timothy Schmalz: I love trying to visually translate ideas and give them a universal, visual, authentic presentation, whether it’s the life of a saint or ideas from the Gospels. It’s extremely difficult, but the end result can be absolutely overpowering.

In the Middle Ages when most people were illiterate, art was the only way they could access the Bible. I think today there’s kind of a parallel to that today – not that people don’t know how to read or write – but it’s finding the time to actually sit down and read something that seems to be difficult for so many people right now. So a piece of art can be a reminder of eternal ideas that you’ve known for years. Among the Coca Cola signs and the MacDonald’s signs, why not have a couple of cues in our visual landscape to bring us an enriched spirituality, right?

Kolbe Times: Your art is very public, in the marketplace, on the streets.

Timothy Schmalz: That’s what I find so fascinating about what I do. When a piece of artwork can be placed in a public place, then you also have to think about artwork as a form of conversion. It almost becomes a visual ambassador to your religion, not only for the people that understand it. It becomes a platform for an introduction. For instance, a sculpture outside a church is making a statement about what’s inside the church. If it’s a poorly done image, it’s kind of saying that what’s inside is predictable and you might not find any benefit from going in. It’s similar to a book cover on a book, in a sense.

Visual ideas can be so powerful. For instance, if one closes one’s eyes and thinks of Mary, usually a piece of artwork will come into that black space. But what type of artwork comes to mind? Hopefully it’s something by Michelangelo – not one of those mass-produced, plastic, red-lipstick figurines of Mary. But you never know!

My point – my basic premise – is to give hands and feet to some of the most eternal ideas of our Christian faith, which is a really big task, as you can imagine.

Kolbe Times: So art can help us focus on ideas in fresh, new ways that make us see things differently and ask questions.

Timothy Schmalz: Yes, it does have that interesting power about it. That brings to mind one of my favourite quotes by Oscar Wilde. I’ve been thinking about this a lot since my “Homeless Jesus” sculpture went to downtown Dublin, installed in front of the Christ Church Cathedral. It’s a quote from Wilde’s essay called “The Decay of Lying”: “There may have been fogs for centuries in London. I dare say there were – but no one saw them. They did not exist until Art invented them.”

Art really has the ability to bring things to our attention unlike anything else.

Kolbe Times: Why have you been drawn to the epic scale, making large statues?

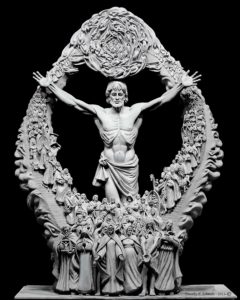

Timothy Schmalz: You know, I used to be so excited about projects like my sculpture “One Body” which depicts the universal Church and has almost 150 saints. But now I’m not focused necessarily on the size of a piece, but on authentically putting forth what I read in the Bible. It can be done with fewer brush strokes, and that’s what I’m learning. The “One Body” sculpture took me nine months, working on it every single day. But I think if you’re open to becoming an instrument, you can achieve something very powerful, and that might possibly be something smaller. That’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about right now.

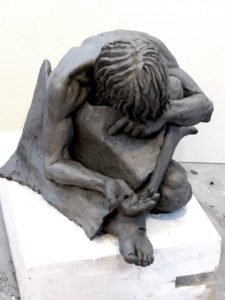

I just finished a sculpture called “When I Was Naked You Clothed Me”. I’ve actually been struggling with it for three years. Part of the process happened when I was in Rome, staying across from the Vatican, in discussions about my Homeless Jesus being placed at the Papal Charities building there. That night, I was sitting, looking out my hotel room in Rome, and I saw homeless people right across the street from me, getting ready for the night. They were literally building things with cardboard. I was mesmerized as I watched them, and I realized that cardboard for the least of our brothers and sisters means a lot more than it means for us. For them, it was not only something to keep them warm and to cushion them from the concrete they were lying on, but also a shelter between them and the world.

The next day I woke up and I realized how to create “When I Was Naked You Clothed Me”. It had to be a naked figure or it doesn’t make sense, but the figure is sheltering himself with a piece of cardboard. It’s one of the most haunting representations that I’ve ever created…and for years I couldn’t figure out how I was going to do it.

The first cast of “When I Was Naked You Clothed Me” is actually going to be at the entrance of St. Peter in Chains Church in the middle of Rome. It’s Cardinal Wuerl’s titular church, and a minor basilica. The Cardinal had a meeting with his church about it, and they love it. They’re placing it in the portico, right as you enter – which is fascinating because the whole work was inspired by Rome, and now the first cast of it is going to this fourth century church in Rome.

Kolbe Times: What impression do you hope viewers will come away with when they encounter a piece like “When I Was Naked You Clothed Me”?

Timothy Schmalz: I am very hopeful. If a sculpture goes to Rome, in a sense it goes to the world. A few years ago I spent a lot of time thinking about the importance of creating Christian artwork today. I realized that with the works of great masters like Michelangelo or Bernini, an added element has been introduced over the centuries about their work – not one they intended – which is that it’s old and antiquated and should be in a museum. I think that having a new creation like “When I Was Naked You Clothed Me” installed at the entrance to the church which is the home of Michelangelo’s famous statue of Moses is making a very powerful and coherent statement that our faith is old but it’s also new…and relevant today.

I think for a long time Christian artwork has been a very poor Ambassador to show how awesome and also how challenging Christianity is. I want to continue to create pieces that are perfect visual ambassadors for our faith, and that don’t over-emphasize the comfort value of our faith. Of course it is comforting for many people, but I think any serious Christian is also blasted by the challenge of Christianity, too. And if a piece of artwork just represents the comfort food, people are not going to get an idea that portrays in true proportion what Christianity is all about.

When I did the “One Body” sculpture, with its 145 saints, I did research and read up on them all. And as I was investing so much energy on how to sculpt them most appropriately, I come to the amazing epiphany that most of these people died horrible, violent deaths. It’s interesting that in our culture we say things like, “Oh, you’re such a saint!” – but if you truly examine our heritage of the saints, it’s fascinating how haunting the lives of these people were. So if I’m sculpting St. Maximillian Kolbe, for instance, I’m not going to have him just smiling and looking like he’s having his picture taken. How many people really know his story? Let’s create a piece of artwork that will make people think, “What’s happening here? Who is this person?”

That’s what I think good artwork should do – inspire us to ask difficult questions, and not just be macaroni and cheese comfort food on a rainy day. When people see “Homeless Jesus” or “When I Was Naked You Clothed Me”, they’re going to be confronted by the Gospel. Hopefully when they see this new Christian artwork, being created today and not centuries ago, they’ll come to the conclusion that Christianity doesn’t belong in a museum…that it’s something alive today.

Kolbe Times: Tell us about your creative process and your typical day in your studio.

Timothy Schmalz: I start sculpting around 4 a.m. and I stop around 5 p.m., every single day. For years now, the only sound I have playing in the background is the Bible being read aloud – on repeat. The audio is a beautiful voice, reading the King James Version of the Bible. So that’s my everyday practice. I’m surrounded by my sculptures, and very visually focused on them. And with the audio playing around me, I’m pulling things down from the air, turning them around, and not only thinking about them but also trying to figure out how they apply to sculpture.

Let me tell you about how a concept recently came about. I’m working on one piece, and then I hear on the audio Hebrews 13:2, where it suggests that you should be nice to strangers, because you never know when you are entertaining an angel. So I’m sculpting one sculpture, and then I hear that verse…and it’s like I almost physically pull those words down from the air and I turn them around in my mind, and they become a table with four chairs around it. One of the chairs has angel wings attached to it – this mysterious chair with angel wings. And I think, that is something that just came out of my studio, right here! So one of my thoughts is that if you immerse yourself in something long enough, things will come out of it.

My prayer is the practice of creating. Sometimes creating feels more like acting in a play, almost like “prayer in motion” as opposed to more passive prayer. So, for instance, instead of just praying and reading about this Irish saint, St. Moling, I’m taking this information and with all my heart, my soul and my brain, I’m trying to take the words and form them into a sculpture. It requires intensity, understanding of the subject matter, and the whole library of all the previous pieces that I’ve done beforehand. That always serves as a great resource. What did I do 15 years ago on a certain Saint? What can I incorporate into my work today? Plus, the pure long hours of being in relative silence, being close to the Bible, every single day, must somehow rub off on me. Hopefully, if it rubs off on me, it’ll rub off on my artwork!

I think that sculptors and other artists have to accept the idea of being alone, and they have to treat the experience with respect – and if possible, consider it prayerful mediation. That’s one thing that can sustain you through the long hours. When you’re in an environment that is essentially like a hermitage, then great things can come from it.

I do secular pieces as well, of course – I’ve done some of the biggest public pieces in Canada – but probably 90% of my work has a Christian theme. I don’t think anything else would sustain me putting this much energy into it for the last 25 years. I have to know that my energy is going into something very, very important.

I love the fact that in the Middle Ages in Western Europe, pretty much the only artwork that was done was Christian artwork. Obviously Christianity isn’t as omnipresent in our western culture as it once was. I think that now the work has to be really powerful because we’re not in an omnipresent Christian culture anymore. Unfortunately I think there has been such negativity in the arts, and also in the relationship between art and Christianity, that a potentially great Christian artist has been hoodwinked at the age of 18 or 19 at art school to think that Christian art isn’t “real” artwork. So much of the artwork we see today is about visual puns and shock. Unfortunately there’s a massive gulf between spirituality and artwork now. My hope is that with my artwork, people will see that connection, that relationship, between art and Christianity – and re-examine some of their ideas.

Kolbe Times: Your art is definitely causing people to think about and discuss the role of art in society, and in their own lives. Your Homeless Jesus, especially, is sparking some pretty interesting conversations.

Timothy Schmalz: Yes, I love it when artwork creates a dialogue. Just yesterday a reporter from England interviewed me about the fact that my Homeless Jesus, which was rejected by Westminister Council in London, is now being appealed by the Methodists in the centre of the city. The Westminster project is very interesting because Westminster Methodist Central Hall is right across the street from Westminster Abbey, and they both loved the sculpture. The Westminster Central Hall wants to place it in front of their church, and they’re being forbidden by the Westminster Council. It’s pretty fascinating how you have criticism about what I would consider one of the most core ideas of Jesus…and a lot of it is coming from Christians. How Jesus is represented is a very sensitive issue for Christians. Some of them are very upset, but it’s almost like a sculpture – and how you approach a sculpture – reveals a lot of the person who is viewing it. When I get a non-Christian or an atheist saying, “I’m not Christian, but I like this sculpture” – and I get that quite a bit – I say, well then maybe you should re-examine Christianity. So it can be an invitation.

Kolbe Times: What are you working on now? What are you excited about?

Timothy Schmalz: I’m working on a piece about the Trinity. I’m working on the clouds right now; it’s a really nice piece. And I’m also about to start another piece about Jesus washing St. Peter’s feet – but St. Peter is missing, so it’s just the representation of Jesus. It’s really cool. What I’m excited about, right now, is that every single day since the start of this year I’ve been listening to the Old Testament, and so I’m going to be working on sculptures that represent some of the most powerful ideas in the Old Testament.

Timothy Schmalz: I’m working on a piece about the Trinity. I’m working on the clouds right now; it’s a really nice piece. And I’m also about to start another piece about Jesus washing St. Peter’s feet – but St. Peter is missing, so it’s just the representation of Jesus. It’s really cool. What I’m excited about, right now, is that every single day since the start of this year I’ve been listening to the Old Testament, and so I’m going to be working on sculptures that represent some of the most powerful ideas in the Old Testament.

One of the sculptures I was working on this past Easter was “Love God with All Your Mind, Heart and Soul”…but I don’t like it. It’s just sitting there, and I don’t know what I’m going to do with it. I have to have enough courage to throw something in the bucket if it’s just not working.

But as long as my mind and heart and soul are, in a sense, focused on glorifying God through artwork, then whatever comes…it can come.

All images courtesy of Timothy Schmalz

Visit Tim’s website or follow him on Facebook.

Timothy Schmalz discussing his statue Homeless Jesus:

A video portrait of Tim Schmalz at work in his studio: