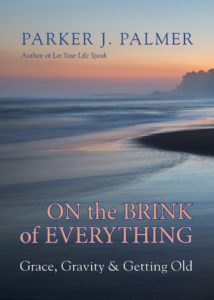

What a treat to chat with Parker Palmer – Quaker elder, teacher, activist, and founder of the Center for Courage & Renewal. He is the author of ten books, which have sold over 1.5 million copies and been translated into 10 languages. On the Brink of Everything: Grace, Gravity and Getting Old is his latest book, published in 2018. Parker turns 80 this month, and we were delighted to talk with him about his beautiful new book, and some of the lessons he’s learned – and is still learning – after eight decades on our planet.

Here are a few audio highlights from our conversation with Parker Palmer, with music by Sergey Cheremisinov (4:54).

Kolbe Times: It’s great to be talking with you today, to catch up on what you’ve been doing and thinking about lately, and to discuss your new book, On the Brink of Everything.

Parker Palmer: Well, thank you so much.

Kolbe Times: To start, I’d love to hear about your recent work with Carrie Newcomer, and your Growing Edge project.

Parker Palmer: Carrie is a very gifted singer and songwriter, and over the last few years, we’ve put on two stage shows, that were ‘song and spoken word’ events. The first one was called Healing the Heart of Democracy: A Gathering of Spirits for the Common Good, and now we have one called What We Need is Here: Hope, Hard Times and The Human Possibility. We’ve presented the first one about ten times, and we’ve done this second one, I think, about six times now, to audiences ranging from 300 to 1000 people. It’s a wonderful combination of things – I wrote the script and we pursued various themes and questions, and Carrie brings along her pianist, Gary Walters, and the three of us do a 90-minute show that we’ve been told really feels hopeful to people.

Kolbe Times: I’ve been exploring the Growing Edge website that you and Carrie have, and there’s so much there! And I love that there are three beautiful songs by Carrie on the website, which can be downloaded free of charge, that she wrote and performed in response to themes in your book. There’s such a depth and richness to her voice. How did you meet her, by the way?

Parker Palmer: Well, that’s interesting you should ask that, because we were trying to figure that out a few weeks ago, actually. And it turns out that it was about 11 or 12 years ago, when she was on the road, doing shows. That can be a lonely life, and she was in a hotel somewhere one night reading my book Let Your Life Speak. And she read some of those pieces, I think, especially the pieces I wrote about the darker times in life. And – this is the kind of person she is – she found out how to get in touch with me and sent me an email telling me how much she appreciated the book and how helpful it had been to her. And then she said, “I’m working on a new album, called Betty’s Diner. Would you write the liner notes for it?” And I was, of course, greatly honoured. I knew of Carrie’s music – not nearly as well as I do now – and I liked it very much. So I wrote the liner notes for the album, and we started corresponding and then eventually getting on Skype and Zoom and then finally meeting in person. She’s been at our house and I’ve been at her house – and so, yeah, it’s become a wonderful friendship and partnership.

“The Brink of Everything”, performed and written by Carrie Newcomer.

Inspired by the book by Parker J. Palmer.

Kolbe Times: Let’s talk a little about your new book. First of all, the title On The Brink of Everything: Grace Gravity, and Getting Old. I love your story of how the title came from your friend Courtney Martin, and her little baby daughter, 16 months old. She described her daughter as being on ‘the brink of everything’. And, you know, that made me think about all the ages and stages in my own life…turning 20, and then turning 40, and now, just this last year, turning 60…they all kind of seemed like being on a brink! A bit scary, but kind of exciting, too. I think it’s a great title.

Parker Palmer: Thank you. I was thrilled when I ran across that phrase in Courtney’s essay, which was on the ‘On Being’ website, where she is a columnist along with me and several others. But when I saw those words, I just thought, my gosh, as I get into my late 70s – I’ll be 80 in February – I’m just like a 16-month-old toddler because my eyes are being open to the world in new ways, which is, of course how Courtney described her daughter. Courtney was taking great joy in watching her daughter walk around open-eyed and full of wonder, and as she said, ‘on the brink of everything’, and that’s exactly where I am, too because I’m looking differently at the past, the present, and the future. And I have done that before, but one of the big differences, I think, is looking at it with really profound gratitude – for everything, even the hard stuff, and seeing, you know, the dark threads that get woven through a life. They too have their place. I think it’s Richard Rohr who says “’everything belongs”, and I was having that real life experience. So that title really helped me transform the ‘brink’ from something totally scary into something exciting, from which you can see stuff you haven’t seen before.

Parker Palmer: Thank you. I was thrilled when I ran across that phrase in Courtney’s essay, which was on the ‘On Being’ website, where she is a columnist along with me and several others. But when I saw those words, I just thought, my gosh, as I get into my late 70s – I’ll be 80 in February – I’m just like a 16-month-old toddler because my eyes are being open to the world in new ways, which is, of course how Courtney described her daughter. Courtney was taking great joy in watching her daughter walk around open-eyed and full of wonder, and as she said, ‘on the brink of everything’, and that’s exactly where I am, too because I’m looking differently at the past, the present, and the future. And I have done that before, but one of the big differences, I think, is looking at it with really profound gratitude – for everything, even the hard stuff, and seeing, you know, the dark threads that get woven through a life. They too have their place. I think it’s Richard Rohr who says “’everything belongs”, and I was having that real life experience. So that title really helped me transform the ‘brink’ from something totally scary into something exciting, from which you can see stuff you haven’t seen before.

Kolbe Times: You know, that makes me think of hiking. We live in Calgary, near the Rocky Mountains. When you come to a viewpoint and see this huge vista spread before you, it can be scary, like being on the edge of a cliff, but it can also take your breath away and let you see things from this amazing new perspective.

Parker Palmer: Oh, I love the metaphor! Because, you know, you labour to get to that place and you can go right to the edge and look down and kind of gasp and think, “I better stand back a bit.” But once you do, you can stop and look around. And then you realize that it’s beautiful, and breathtaking.

Kolbe Times: Speaking of Richard Rohr, I know in his testimonial at the front of your book, he mentioned that our culture is in need of true elders, and that you are one person who has clearly earned that title. And, you know, I was realizing that another thing I appreciate about you and your writing is that you are an honest elder. You are not afraid to share what you’ve learned from your mistakes, and laugh at yourself, and keep growing. Is that kind of self-honesty something that has developed as you’ve gotten older?

Parker Palmer: That’s a wonderful question. One thing I know for sure is that – to the extent that it’s possible without implicating other people or telling their stories – is that trying to be honest with myself, and then honest with others, has been a major step forward in my life. I think probably going back to my 40s, when I dealt with my first bout of clinical depression –I’ve had three major deep dives into clinical depression in my life, the last one when I was in my mid 60s – I’ve learned each time that while depression is complicated, and some of it is genetic and biochemical, some of it is situational. And I think each time, I’ve learned a new lesson about the importance of showing up as who I really am in the world. So being honest with myself is, I think, an act driven by this fundamental human need to feel at home in my own skin, and at home on the face of the earth. And we can’t feel that way if we’re faking it and pretending to be someone we’re not. If you do that, the constant feeling is one of fraudulence, along with the fear that other people are going to find you out to be a fraud. That’s not a good way to live. You’re not at home with anything that way. Thomas Merton once said, in his typically brilliant way, that most people live lives of self-impersonation.

When I read that sentence, in one of his journals, I thought, “Oh, my gosh, how brilliant can you be!” – and I also recognized it in myself. One of the keys to living an examined life, as Socrates would say, is that when something rings a bell with you, to recognize yourself in that mirror. So I really think of this business of being as honest as I can in public as therapy. However, I should mention that following my first depression, it took me a decade before I could write about that, or speak about it in public. I’m sure that was partly because I was embarrassed; I didn’t want to, you know, “appear weak”. I was still dependent on being the good guy, the bright and shining guy, the knight in shining armor. I was getting my identity from that falsehood. Now I understand that it’s a false assumption that you’ll appear weak if you acknowledge who you are and what you’re going through. It actually takes a lot of strength! But it took me a decade to realize that, because I did not yet have that experience of darkness being integrated into my sense of self. It’s important to fully integrate the dark experiences, the shadow side experiences into yourself, so that you’re able to stand in front of people and say, I am all of the above, I am my darkness, and I am my light. And I am my gifts, and I am my weaknesses. I am my accomplishments, and I am my failures.

But I also want to say that it’s very important to be patient with ourselves and with others, and wait until there’s a readiness.

Kolbe Times: I think as you have become more integrated and “at home in your own skin”, and as you demonstrate those qualities, it’s really therapeutic for the rest of us. It encourages us to do the same.

Parker Palmer: I appreciate that very much. You know, this new book is my tenth book. I’ve published a lot of words, and an interesting fact is that there is no single piece of my writing to which I’ve gotten more response than a chapter about depression that appears in my book Let Your Life Speak. I hear from so many people about it – either folks who suffer from depression, or those who live with folks who suffer from depression. People express their gratitude to me for saying out loud what’s not easy to say. So it turns out to be therapeutic and comforting for others, as well as for me. That’s a gift for which I’m very grateful.

Kolbe Times: I want to mention how much I enjoyed all the poetry in your new book, some of it written by you. There was one poem that really struck you, and really struck me as well, by the Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980. The poem is called “Love”, and it just seemed so down-to-earth and meaningful – and so beautiful. Can you talk about that poem a little?

Parker Palmer: Yes, I have a vivid memory of running across that poem for the first time, and realizing that these are important words. I realized that I needed to pay attention to them especially in the context of that sort of vexing, often egotistical question that we ask ourselves: “Does my life have meaning?”

Milosz begins his poem this way, as you know:

Love means to learn to look at yourself

The way one looks at distant things

For you are only one thing among many.

And whoever sees that way heals his heart,

Without knowing it, from various ills.

When I read that, I thought, well, I know that it is possible to make yourself ill from asking this question, “Does my life have meaning?” – especially when you’re older, because I’ve done it myself. I think a lot of people wrestle with that question as they age. People look back, you know, and they can’t find those big things or big achievements, that our culture says are the only things that count. But – and this is an old lesson from all of the spiritual traditions – if you can start to free yourself from the grip of the demanding, overweening ego, which always wants to be seen as “special”…and we seem to have a president in this country right now that feels that way about himself…when you can see yourself in perspective, suddenly that question “Does my life have meaning?” transforms. It’s a hard thing to describe, but where I feel it most is in the wilderness, out in the woods, or on the edge of big water, or by a beautiful stream, far away from traffic and city noise. When I’m out there I feel that there are all these life forms around me, sacred and important, just as I am sacred and important, somehow, things come into proper focus. I’ve been blessed to have many opportunities to hike in different natural environments. And one time I remember I was hiking in the high desert, outside of Taos, New Mexico at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. And I was at a point where I was watching very carefully because there were no human structures or human activities going on to help me orient myself. So I was in danger of getting lost, the way I often do. So I was really trying to pay attention to the environment. And suddenly I was struck with this – it’s hard to know how to describe it – this moment in which I realized bone deep that the cosmos was utterly indifferent to me; I was so tiny, I was a speck on this vast landscape…and yet at the same time, it was utterly compassionate toward me, and forgiving of me. And somehow those two things went together in a beautiful way that I was not under the microscope and being scrutinized for my faults and my failures, but I was accepted as one thing among many, and all I had to do was accept myself the same way.

Kolbe Times: I can see there’s a real freedom there as well. It’s very counter-cultural, because we have this celebrity-worship thing that’s so strong, and we’d kind of all like to be celebrities. But if we think of ourselves as just “one among many”, it allows us to relax a little! That reminds me of something else in your new book that you wrote about. A therapist once helped you understand that “down is the way to well-being”. You later paraphrase that as the idea of having “a life on the ground”. Can you expand on what that means to you?

Parker Palmer: Yes, thank you, that brings back a really important moment in my journey with depression, and in my life journey. I was seeing this therapist about my depression, and he listened to me for quite a long time. And finally, after the seventh or eighth meeting, he said, “If I could mirror something back to you, Parker, it seems to me that you are imaging depression as the hand of an enemy trying to crush you”…which is indeed how it felt. But he said, “Would it be possible for you to image depression as the hand of a friend trying to press you down to the ground on which it’s safe to stand?” He was a very wise man and a good therapist. He didn’t give me a lecture; he just sort of planted that image with me. And I think he trusted that I could work with it, which I did. And we talked about it more in the subsequent weeks and months. But what I came to understand is this: I had been living ‘at altitude’, and I remember trying to identify the ways in which I had been doing that. I was living at altitude because of my ego, which wanted to be at the top of the tower. I was living at altitude because of my intellect, which wanted to think its way through everything, and you can’t think your way out of depression. I was living at altitude because of my high ethic, which wasn’t coming from inside of me; it was just a bag full of ‘oughts’ that were inherited from God knows where. And I was living at altitude because of some misunderstandings I had about spirituality being sort of a Superman “up, up and away” kind of thing.

Well, that’s a lot of altitude that I’ve just named. I was probably in the stratosphere at that point, where the oxygen is very thin. It’s not fit for human life. But the big point is that if you live ‘at altitude’ and you trip and fall, as we all do on a pretty regular basis, you have a long, long way to fall, and you might kill yourself.

Depression can sometimes be imaged, especially depressions that end in suicide, as falling a long, long way down. But if the spiritual quest is to get your feet on the ground, and the intellectual quest is to use your mind on the ground, and the ethical quest is to find those values that come up through your own root system, and you really keep working with your ego, to keep it from making you into a gas balloon, and you live on the ground, then you can fall down ten times a day and not kill yourself. You can get up, dust yourself off and proceed. And that image stayed with me in a really, really helpful way.

Years ago I studied the work of Paul Tillich, the great theologian, when I was in my 20s at Union Theological Seminary in New York, and was too young to understand what he was talking about. For Tillich, the image of God was ‘the ground of our being’. I think I understand now why those are important words. It’s groundedness that I think we’re all seeking; solid ground under our feet.

Kolbe Times: So many great images in that. Another part of your book that made me laugh out loud was when you describe that some people are “contemplative by intention” – folks who are practicing contemplative disciplines day in and day out, and really benefit by it. But you describe yourself as a “contemplative by catastrophe”…and then mention that you don’t recommend this path as a conscious choice. I loved that part! Can you talk about what you mean there?

Parker Palmer: Thank you again; great question. You’re going right to the heart of a number of things that I care about in this book. And I’m glad it made you laugh out loud. Maybe my next career will be a stand-up comic. Anyways, I spent time in my 20s and 30s trying to be that classical, contemplative, you know – sitting cross legged and chanting a mantra, or doing the monastic thing, even though I was married and had three kids. It wasn’t working for some pretty obvious reasons, and I got to thinking that if I can’t do contemplation as it’s conventionally understood, how can I hold that reality in some meaningful way? So I got to thinking about the functions of contemplation. I came up with this notion that in every tradition that I know anything about, the function of contemplation is to help people penetrate illusion and touch reality. I’ve talked about that with a lot of people from many different traditions, and nobody has ever challenged it. So, if that’s what contemplation is meant to do, then do I have other ways of penetrating illusions about myself, and the world, and our connection with each other – and then touching reality that is solid ground on which to stand? And I thought, “Yeah, I do – and a lot of it is about failing, messing up, and getting it wrong.”

I realized that when I succeed, I don’t try to penetrate any illusions. Instead, I generate illusions – especially illusions about myself: “Oh, I must be really cool, because I just succeeded at something”, or “I sold a lot of books”, or “I got a standing ovation for a talk.” To go back to some of those phrases which I love from my grandparents’ generation, “I must be the cat’s meow or the cat’s pajamas.” I don’t learn much when I succeed.

But when I fail, that’s when I stay up late and ponder and chew on stuff and try to figure out what I got wrong. You know, “I thought I had such a good speech all ready”, or “I thought I knew just the right thing to say to this person, and it all blew up”. What did I get wrong? That’s when I’m penetrating illusions about myself. That’s when I’m trying to figure out how to connect more creatively with what the world needs, and that’s when I come closer to some kind of truth. Those are the experiences that I think of as being ‘contemplative by catastrophe’. It’s when I’ve been involved in making something really unfortunate happen – and it’s often more unfortunate for me than for other people – or when I have let other people down. And in those moments, I’m functioning as a person who is penetrating illusion and touching reality much more than when I’m doing everything perfectly.

Kolbe Times: Yes, it really strikes me how healthy and positive it can be when we find the courage to look at our failures and acknowledge them and try to grow from them, instead of beating ourselves up, or just refusing to even admit them.

Parker Palmer: Yeah, and I think, in fact, that’s the way most of us grow – but the ego does a lot of kicking and screaming about that. I think it’s ancient wisdom that if something really bad happens in your life, if you go through something really tough, the best way forward is to ask, “What can I learn from this, that will enrich my life and make it fuller going forward.” That’s why it’s very common, I think, for people to experience personal tragedies, like the loss of the most loved person in their life, and go into that long underground period of grieving and feeling like life will never be worth living again, and yet emerge from that, down the road somewhere, with the realization that not in spite of the loss, but precisely because of the loss, they have become bigger people. They have become more compassionate, more understanding, more grateful, more giving, more generous with others…because loss has taught them something important about what it means to be human.

I’m very fond of quoting one of my Canadian heroes, Leonard Cohen, and those wonderful lines in his song Anthem: “Ring the bells that still can ring, Forget your perfect offering, there is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.” He summarizes something very important, which is forget these silly notions of perfection, and that you’ve got to take care of everything, just “ring the bells that still can ring”. They’re muffled for a while in the wake of great loss, but eventually some of them will ring clearer and truer than ever before.

Kolbe Times: You also mention in the book – and I think it’s so true – that just the process of growing older, and coming to terms with the soul-truth of who we really are, a complex mix of darkness and light, results in our egos shriveling up somewhat. And then you write, “Nothing shrivels a person better than age. It’s what all those wrinkles are about.” Love it. But I sure see that in my own experience, as a female in my early sixties now, that in many places I am kind of invisible. The interesting part is that I’m also starting to realize that in many ways that’s a good thing! I can stand back, and watch, and learn, and be a support to others. It’s not all about me! I can relax – and to quote Czeslaw Milosz again – just be “one among many”.

Parker Palmer: Yes, exactly. I feel the same way. And it’s interesting that invisible people, you know, often see more of what’s really going on, more so than people who are in the middle of the action. In the book I quote Kurt Vonnegut who said through a character in one of his novels, that out on the edge you see all kinds of things you can’t see from the centre. That becomes clear in old age. You’re no longer at the centre of the action. Many of us have retired from one thing or another, maybe several things. In my case, I’m no longer flying around the country all the time giving talks and workshops. I do some of that, but not nearly as much as I did for 40 years. And you know, it gives me a perspective on things that was sometimes hard to come by when I was constantly on the road, because I was using so much energy to just sort of keep it together and then come home and recuperate, and then start getting ready for the next gig. I can now give that energy to different things that especially involve being appreciative and being generous and trying to become more insightful.

Kolbe Times: That makes me think of how near the end of your book you quoted the psychologist Erik Erikson, who says that we have this choice as we grow older between generativity and the alternative, which is stagnation. You point out that “generativity means more than creativity; it means turning toward the rising generation – not to advise them but to learn from them and gain energy from them.” Can you talk a bit about that experience, and what it has meant for you personally?

Parker Palmer: I’d love to. Erikson was a really interesting guy, and he developed a theory of adult development. A lot of people have theories of child or adolescent development, but he developed a stage theory of adult development with eight stages, each of them defined by a polarity or a choice to be made between two poles, and so I think in his next to last stage of life, he said that the existential choice is between generativity and stagnation. It was years ago that I read that, but I remember thinking, wow, he’s onto something, because I see a lot of older people who become stagnant, you know – just recycling the same daily routine. They don’t think any new thoughts, they don’t reach out for any new influences in their lives, and that stagnation is a sort of slow and sad death. But it took me a while to understand that by generativity, he didn’t just mean creativity in general, like taking up a hobby or joining a club. He literally, as you said, meant turning around and reaching out to the younger generation.

I’ve been lucky because I’ve had a life in which that opportunity of being related to the younger generation was kind of baked into a lot of the things that I did, as a teacher, as a writer, as a traveling speaker, and so forth. I was often working with people younger than I, and then in my work with the non-profit that I founded, The Center for Courage & Renewal, I was always actively encouraging and recruiting younger people to get involved. That’s a practice that I’ve kept up, even as I’ve retired from my role at the non-profit and being on the road less. I still work with people younger than I, anywhere from 15 to 30 or 40 years younger, because I get so much out of it. I think of this rising generation as sort of the advanced scouts for me. They’re living out on a frontier or horizon that I can’t see that clearly. If you’re born in 1939 as I was, there are things that you can’t see about the contemporary world as clearly as someone can who was born in 1989. I need their eyes and ears and mouths to tell me what they’re seeing, because that same horizon is coming at me whether I know it or not.

The typical complaint of elders is that the younger generation is going to hell in a handbasket. “What happened to all the traditional values and the ways we used to do things, they were the best, blah, blah, blah.” You know, in my generation, when I was a young man, it was the Beatles who were the toxic influence on the minds of our youth! Well, the Beatles were actually a lot of fun! I don’t know all the music or the dance moves or the lyrics of today’s music, but I can ask younger people to help me understand all that and learn a lot in the process – learning the lyrics and the dance moves metaphorically as well as literally.

Of course, in that exchange, they also start asking me questions. And sure, they say that they benefit from the wisdom of my experience. But all of that has to start with the elders approaching the younger people, not with our advice for their lives, because we can barely understand the context in which they’re living their lives. The first move is up to us saying a very simple statement: “I’m really interested in you and in how you’re experiencing your life. Would you be my teacher? Would you be my mentor?” You can’t always convey that message in such direct language, but you can express it and convey it in many ways.

I think there’s this fear that passes between the older and younger people. The older people feel like young people see them as being over the hill. And that’s a terrible feeling. But younger people look at us as if we don’t care about them – you know, that we have resources, but we’re not offering those resources to them. We’re not asking them what life is like for them, and where things are pinching and where they’re hurting, where their hopes are and where their energies are. When we can break through that mutual impasse which neither the older nor the younger want to be in, something new happens and it’s good for everyone. And I just find that it’s hugely enriching.

Kolbe Times: That’s so inspiring. And I think that’s something that we have to be intentional about.

Parker Palmer: Yes, absolutely. I spent a year as a visiting professor at Berea College in Kentucky, which serves the young people of Appalachia who often have problems with low self esteem. I was teaching a course for senior students that was called Where Do We Go From Here? It was kind of a vocational discernment and decision-making course. And in the middle of that course, I told them that I had an assignment for them. I said that I wanted them to reach out to some older person in this area who is doing the kind of work that you think you might like to do. If you want to go into banking or economics, reach out to a banker. If you want to work in the area of social change, reach out to an older activist. If you want to teach at a college, reach out to a college professor. And I told the students to make it clear that you aren’t looking for a job interview – you simply want to find out how they got to be who they are, and how they got to be doing what they’re doing, because you’re interested in the field and you figure that they could tell you a lot about it. My students said, “Oh, they’re not going to be interested in talking to us.” And I said, “Let me tell you something – there is nobody who is older than you who won’t feel that it’s a huge compliment for someone who’s in their early 20s to reach out to them and say, “You interest me and I want to learn from you.” And I was right.

I think that all of us underestimate – radically underestimate – the power of expressing interest in another person. There’s a wonderful poet named Elizabeth Alexander who has this very simple line in one of her poems that I think about a lot. She asks, “Are we not of interest to each other?”

Yeah, of course we are! So let’s act on that – and intergenerational relations are one way to do it.

Kolbe Times: That’s so true. Unfortunately there’s a real disconnect sometimes. And, you know, all it takes is a little courage, to step out and approach somebody and just be receptive and attentive. More often than not, people are thrilled!

Parker Palmer: Exactly! They think, “Wow, this is amazing! Somebody is actually interested in me!”

Kolbe Times: Thank you so much for spending so much time with us today. It’s been great fun, and really lovely talking to you. I also want to thank you for writing this book. I know I’m going to be re-reading many of the selections in it for many years to come. I’ve already ‘dog-eared’ so many pages!

Parker Palmer: I appreciate your interest in my books and my work very much. And you know, it’s returned full measure – I really enjoy your magazine. And it’s been wonderful talking with you today.

All photos courtesy of Parker J. Palmer.