Bouncing back from life’s traumas and stresses is never easy. Plenty of studies show that a primary factor in developing resilience is having a history of caring, supportive relationships in our lives. Those relationships are like the old rope we keep in the trunk of our car, that we pull out and put to good use when we need to tie things down or hold things together.

But what happens when we’ve lost that rope…or if we never had one in the first place?

I remember once when we bought a small used shelf from an online ad – which from the photo looked like it would fit easily into the back seat of our Honda Accord, with a little pushing and shoving. Well, when we got to the seller’s house, that cute little shelf turned out to be quite a bit bigger than it looked in the photo, and, as you probably guessed, it definitely didn’t fit into our back seat. No problem, we said. We’ll just drive home – slowly – with the shelf tied to our roof, we said. And then we discovered that the old rope that was always tucked away somewhere in our trunk…was missing.

Luckily, the friendly former owner of said shelf came to our rescue, gave us all the rope we needed, helped us tie the thing down, and we went on our (slow) merry way. We learned a lesson (try and be more prepared!) and it all turned out well in the end.

This kind of situation can be no big deal when we are in good mental shape, and have a healthy history of things working out okay. Eating a little humble pie and asking for help can actually be a very good thing on occasion. But for many of us without the emotional capacity at times, or with a chronic mental illness – no rope in the trunk, as it were – developing resilience can be a very big deal.

In other words, resilience is a quality in short supply for a lot of people, especially those with chronic depression, schizophrenia, traumatic brain injury, PTSD, or other debilitating mental health conditions. And it’s something that a lot of us rarely think about.

The Canadian Mental Health Association tells us that officially, in any given year, one in five Canadians will suffer from a mental health problem or illness…though the numbers are probably closer to one in four simply because men tend to under-report things like depression and anxiety.

Frank Kelton is the Executive Director of Potential Place in Calgary, a local charity that helps hundreds of people with chronic mental health problems, many of whom are short on resilience.

“Most of us know someone in our family, or it could be ourselves, who have struggled with mental health issues,” says Kelton. “A lot of folks with chronic and persistent mental illness notoriously isolate themselves. So getting them out from their homes, getting them to a social agency, especially a psycho-social rehabilitation agency like ours, is important. Sometimes that’s the best and the most they can do in a day at the beginning of their recovery.”

Even if it becomes obvious to others, mental illness can be hard for the sufferer to acknowledge and identify. Kelton points out that often they have been misdiagnosed, or not diagnosed at all, well into their 20s or even 30s.

Other times, it is a mystery to everyone involved.

“We’ve met with lots of parents who have told us that they had no idea what was going on with their son or daughter,” explains Kelton. “In the case of schizophrenia, it is not well articulated in everyday parlance and conversation around symptoms and so on. And it doesn’t help that there’s such stigma and so many misconceptions out there – you know, that anybody who has schizophrenia is probably a serial killer.”

It’s often difficult for a person stuck in the middle of mental illness to find hope and resilience by themselves. Reaching out to others is tough, especially when programs and services are being cut or are not that easy to find.

That was the story for a number of mental health patients in New York City in the late 1940s. They were discharged from Rutgers Psychiatric Hospital, and so decided to meet together on the steps of the New York Public Library for fellowship. Their meetings led to the formation of Fountain House, which became a club that welcomed any former mental health patients needing help and friendship. Subsequently, in the 1950s, Fountain House took on professional leadership, and began to emphasize returning to employment as well as providing social support…and developed into a international network of psycho-social rehabilitation centres. Among many important innovations, the Clubhouse Movement injected strong ideas about optimism, self-help, personal dignity, and experiential learning in real-world settings.1

Today there are more than 300 accredited Clubhouses in over 30 countries. (You can check the Clubhouse International website to see if there is a Clubhouse near you.) Potential Place in Calgary is one of them.

“When people get discharged from hospital with chronic and persistent mental illness,  they need a structured program to go to,” says Kelton. “But they need a program or place that connects them with others in a meaningful way, and that provides them with a sense of ownership. The founders of that first NYC Clubhouse knew that everyone needs a place to feel welcome, a place to socialize, to work, and to come back to.”

they need a structured program to go to,” says Kelton. “But they need a program or place that connects them with others in a meaningful way, and that provides them with a sense of ownership. The founders of that first NYC Clubhouse knew that everyone needs a place to feel welcome, a place to socialize, to work, and to come back to.”

What sets the Clubhouse model apart from other programs or other approaches for people with chronic mental health issues? First of all, it’s not a clinical model. People are not treated strictly by their medical diagnosis, or defined by their conditions. The members of the Clubhouse are all equal, be they sufferers of mental health conditions or staff. There is little or no hierarchy. Instead, there are standards, which set forth the values people with lived experience require to function together and create a safe and healthy community.

“Here at Potential Place, we acknowledge members’ abilities and put them to work running and managing the operations of our Clubhouse,” explains Kelton. “We have a clerical unit, we have a café, which is a magnet for our young adults, and we have a marketing and communications unit with the full green screen for doing news, weather and sports webcasts.”

Potential Place also advocates for housing for its members. In addition, they have two small apartment buildings that house 25 members, who live independently.

Getting and holding down a paying job is vital to recovery, according to Kelton. The employment program model at Potential place offers many benefits to Clubhouse members, and to businesses in the community as well. Potential Place ensures that every Clubhouse member who fills an available position in a business is at least as competent and capable as someone they would find through other means. Staff at Potential Place help train their members, at no cost to the business, to fill available opportunities. The employment program is anchored around part time entry-level positions, usually between six and nine months in length.

“Working in a job really increases our members’ self esteem, they’re more independent, they’ve got a paycheck, and we put their names and pictures up on a board that gets highlighted and talked about,” says Kelton. “That really encourages other members to participate in our employment program, and get real jobs with real paychecks. And those are generally the transitional employment jobs; they’re generally starting jobs at minimum wage or a little better. We ask that the employer pay what the going rate would be for somebody that they would hire themselves.”

Practical help with transition back into the workplace is often missing for people with mental health issues, according to Kelton, but it is vital to Potential Place’s approach. It can be a difficult step forward for many, but members are given lots of support, and can break in gradually, according to their ability and preparedness.

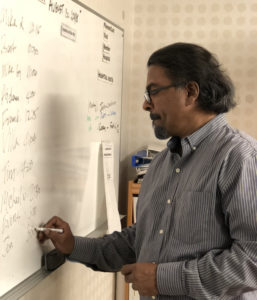

Potential Place staff Villa Kulasegaram and others help members with scheduling and other practical supports

”We see there’s more and more independence as the months march on,” remarks Kelton. “And we’ve seen many times when we’re ready to rotate somebody new into a position, that the employer will say, hey, we really like this person – can we can we keep them instead?”

Primary to the Clubhouse model is its collegiality.

“It’s very egalitarian,” points out Kelton. “Unlike a doctor-patient relationship, where there can be this power imbalance, we’re all just folks – “colleagues”, as we call each other.

For the most part, I’m sure when you walk in you can’t tell who are the staff members here.”

There are a lot of benefits to this model. Inclusion in the community and developing strong relationships has been proven to be vital to fostering resilient, integrated mental health.

“At the end of the day, our goal is to take people out of the darkness, and improve the trajectory of their mental health by putting them to work, both in jobs out in the community and running the operations of the Clubhouse,” says Kelton. “For many, the Clubhouse has become their family. It’s a place where they come to talk with their dearest friends, and to meet with staff to socialize and talk about the progress in their lives. This may sound ironic, but hopefully some of them we eventually won’t see anymore, because they’re busy living their lives, working in the community or going back to school.”

Today, almost 80 years since that group of displaced mental health patients with nowhere to go started meeting on the steps of the NYC Public Library, there are Clubhouses like Potential Place all over the world, with 17 in Canada.

Kelton thinks that’s not enough.

“I think we should have a Clubhouse in every community!”

Ultimately, it’s about providing people with a place where they feel at home, in a positive environment with caring friends – a place to make goals and work toward them, to give back to others, and to gain the self-esteem that helps us navigate the ups and downs of life.

Ultimately, it’s about providing people with a place where they feel at home, in a positive environment with caring friends – a place to make goals and work toward them, to give back to others, and to gain the self-esteem that helps us navigate the ups and downs of life.

We all need a strong rope in our trunk sometimes.

- Becker, Deborah and Drake, Robert; A Working Life for People with Severe Mental Illness; Oxford University Press, 2003; pg. 11.

For more information, visit www.potentialplace.org

This was such a pleasure to work on.

And you did a great job!