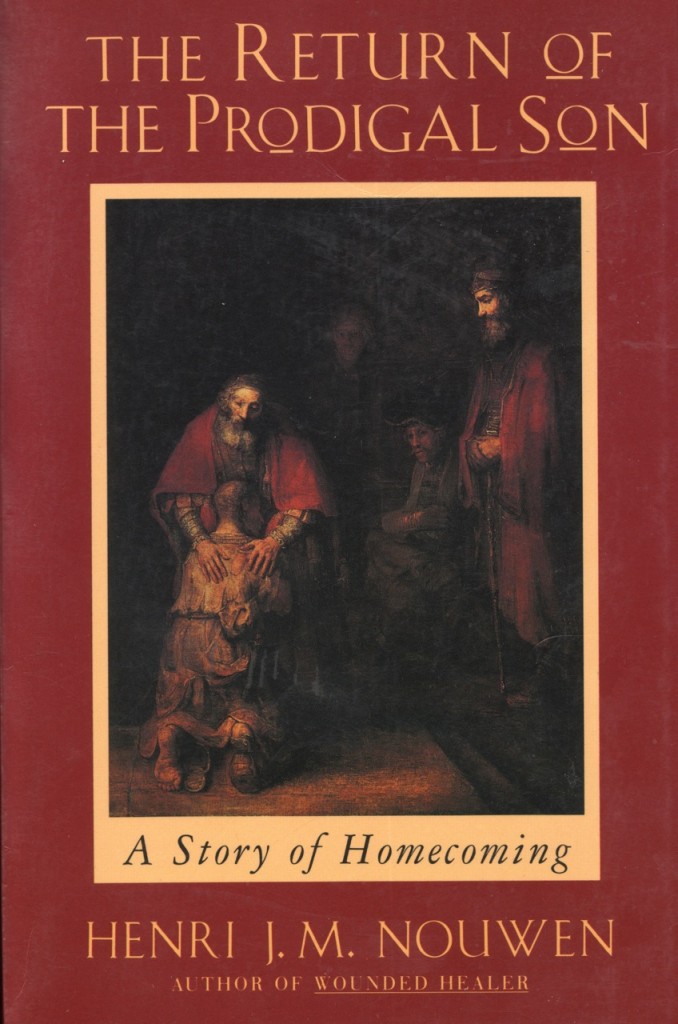

With the theme of “Mercy” for this issue of Kolbe Times, it seemed the perfect chance for me to read and review The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming by Henri Nouwen. I’ve long been a fan of Nouwen’s books, but somehow this one never made it to my bedside table. Based on Jesus’ powerful parable of a wayward younger son returning home to face his father and older brother found in Luke 15: 11-32, this book is a captivating exploration of forgiveness and restoration.

With the theme of “Mercy” for this issue of Kolbe Times, it seemed the perfect chance for me to read and review The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming by Henri Nouwen. I’ve long been a fan of Nouwen’s books, but somehow this one never made it to my bedside table. Based on Jesus’ powerful parable of a wayward younger son returning home to face his father and older brother found in Luke 15: 11-32, this book is a captivating exploration of forgiveness and restoration.

Henri Nouwen was a Dutch-born priest who studied psychology and theology, and then went on to teach at various universities and theological institutes, including Notre Dame, Yale and Harvard. Nouwen was the author of over forty books, and he often wrote in a disarmingly intimate style, exploring our human need for meaning and intimacy. Nouwen suffered from bouts of depression, and he wasn’t afraid to write about his struggles and his very personal spiritual insights, which is precisely what makes his books so potent and helpful. In an interesting tie to our cover story about the fiftieth anniversary of L’Arche, Nouwen spent his last ten years living and serving at L’Arche Daybreak Community near Toronto, before his sudden death of a heart attack in 1996.

The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming was first published in 1992, but the story told in the book begins ten years earlier. After an exhausting lecture tour across the U.S., Nouwen decided to visit the L’Arche community in Trosly-Breuil, France for a time of rest and to visit his new friend Jean Vanier. While there, he happened to see a poster of the famous painting by Rembrandt entitled The Return of the Prodigal Son. Nouwen writes that his heart leapt when he saw it. He recalls, “The tender embrace of father and son expressed everything I desired at that moment.”

And so began a sometimes painful but very fruitful spiritual adventure, which Nouwen shares with us in this beautifully written book. After seeing the poster, he embarked on an in-depth exploration of the themes in the parable, Rembrandt’s life, the painting itself, and his own self-image. Nouwen not only read all the biographies of Rembrandt and historical studies of the painting that he could find, he also travelled to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia to see the original painting. As is the case with many of his books, Nouwen openly shares the very personal revelations that arose out of his research and mediations. He begins the book by drawing comparisons between the younger son in the parable who flees from his loving home, and his own life:

“Over and over again I have left home. I have fled the hands of blessing and run off to faraway places searching for love. This is the great tragedy of my life, and of the lives of so many I meet on my journey.”

Nouwen later starts to wonder if perhaps he is also much like the elder brother in the parable, and this opens a whole new avenue of exploration and self-reflection. Nouwen does a brilliant analysis of how deeply rooted the “lostness” of the elder brother is, and how hard it is to return home from there. He writes:

“At the very moment I want to speak or act out of my most generous self, I get caught in anger or jealousy. And it seems that just as I want to be most selfless, I find myself obsessed about being loved. Wherever my virtuous self is, there also is the resentful complainer. I am faced with my own true poverty. Can the elder son in me come home?”

In the last third of the book, Nouwen focuses on the father in this parable. He marvels at God’s eagerness to “run to welcome his returning son and fill the heavens with sounds of divine joy.” Nouwen has a surprising and life-changing revelation – that perhaps he is being called to become the father: “I now see that the hands that forgive, console, heal and offer a festive meal must become my own.”

Nouwen does a marvelous job of deconstructing elements of the painting itself – the placement of the characters, the lighting, the symbolism of the clothing, the representation of the father’s hands, the subtle use of colour, the facial expressions. It’s both fascinating and very enriching to get lost with Nouwen in these aspects of the painting, to examine their significance, and to speculate on what Rembrandt might have been trying to convey.

Through his clear and engaging writing style, Nouwen gently enticed me down a path of my own self-reflection. What is Jesus saying to me through this parable? Am I most like the younger son or the older brother? Are there some situations in my life where my hands could become more like the father’s hands? The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming is a both an inspiration and a guide, lighting the way towards a deeper understanding of ourselves, and of our merciful God’s longing to be fully reconciled with each of us.