The wound is the place where the Light enters you.

-Rumi

In our collective history, much of humanity has suffered from various forms of trauma (what we now call PTSD). According to Franciscan priest Richard Rohr, “Trauma is an intense emotional reaction to an event that is too painful or frightening to process, which leaves us in perpetual survival mode.” Bessel van der Kolk, psychiatrist and author, describes its essence as “something overwhelming, unbelievable, and unbearable.”

Trauma, especially when experienced in childhood, becomes our psychological wound. This wound, imprinted as negative emotional patterns – the “Wounded Child” within – can be passed from generation to generation.

My family history exemplifies a case of intergenerational trauma, where traumatic experiences were passed on from trauma survivors to their descendants.

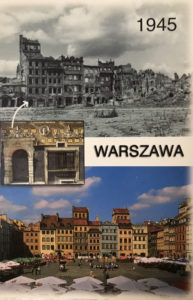

I was born and raised in Poland – a country that has been historically threatened by its neighbors, partitioned in the 18th century, and eliminated as a sovereign state for 123 years. Polish territory was also one of the major arenas of the two world wars. This means that a great many previous generations that I am the descendant of, including the generation of my parents, were subjected to the trauma of war and its long-term consequences.

These experiences and the reactions to them have been storming through generations in a ripple effect, and they have deeply (though mostly subconsciously) affected me, and even – to some degree – my children.

When Germany invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, starting WWII, my grandparents fled to England, leaving behind their only child – my then 11-year-old mother. She remained in Poland with her old and sick grandmother whom she had to care for. As residents of Warsaw, they both survived the nightmare of the Warsaw Uprising, a major WWII operation carried out by the Polish Underground resistance movement against the German occupation. For two months, my mother and my great-grandmother spent most of their days and nights hidden in the basement of their apartment building. The incessant sounds of the sirens warning of continual aerial bombardments of the city by the Luftwaffe, and the loud explosions of bombs falling on buildings were part of their everyday experience. The city was in flames, visible from 100 kilometers away. Food and water shortages had reached dangerous levels. There were mass executions; 200,000 Warsaw civilians were killed during these two months.

After the downfall of the Warsaw Uprising, the Warsaw residents who had survived were deported to a transit camp in Pruszków, a town near the city. There, SS and Gestapo segregated the Poles who were then either deported to forced labor in Germany (which would have been my mother) or sent to Auschwitz Concentration Camp for extermination (which would have been my great-grandmother). Thankfully, a family member was able to bribe the Nazi guards, and they were let go. They were free … however, they didn’t have a place to live, they had no money, no food, and zero possessions. After spending a few nights outside in a field, they were taken in by strangers who let them stay in a spare little room of their house. They lived there for a few months until the Germans capitulated and the Russian Red Army invaded Poland, calling themselves “the liberators”. The Red Army soldiers forced their way into the house where my mom was staying. They took all possible possessions that were in the house, including bedding and pillows, and attempted to rape the women; thankfully, my mom was able to hide in the bathroom.

In May 1945 the war was over. However, the life of my family had been changed forever. My mother’s parents never came back to Poland; they immigrated from England to the United States and lived there until they passed away. My mom was only able to pay them a short visit in the United States when she was 31 years old; the communist regime had denied her a passport for years. At that time, they had been separated for 20 years. My great-grandmother immigrated to Portugal to join her other son. My mother never saw her again.

My mother remained in Poland, forever separated from her family: her grandmother, mother, father, uncle, aunt, and her only cousin. They corresponded for years, but unfortunately, my mother had become their emotional outlet; their letters expressed homesickness, despair, and depression. They wrote about their struggles with alcoholism, problems with assimilation in a new country, and loss of their socio-economic status (the entire family – extremely wealthy before the war – lost everything. The communist regime in Poland took all their possessions, including factories, lands, bank savings, etc.). They also notified my mom of several suicide attempts in the family, one of which – by her only cousin – was successful.

Poland became one of the satellites of communist Russia, and because my mother’s parents lived in the United States, the communist regime suspected her of being a spy. This was the era of the cold war. She was interrogated by the Polish Security Service on many occasions.

I was born 11 years after the war, in a land soaked in blood, in a city still in ruins, to a mother experiencing full-blown PTSD.

A traumatized mother, overwhelmed not only with her own unspeakable trauma but also the trauma of her entire family, and deprived of internal and external resources that would help her understand and process her reactions, cannot create a psychologically safe place for her child. Her own inner child was deeply wounded.

During my childhood, I experienced things that a child should never have to experience. Intergenerational sickness was at play. A child is not supposed to be threatened and diminished verbally, abused physically, and belittled mentally. To survive, you push the memories of these unbearable experiences deep into your subconscious, and by the time you’re an adolescent, you forget about them. Your nervous system, however, remembers. To quote Dr. Bessel van der Kolk again, “Your body keeps the score.” One price you pay for trauma is often a separation from your body. You become stuck in a “fight, flight, or freeze” response. While not aware of it, you somehow continue to be “there”, not being able to be “here”, and you are unable to feel fully alive in the present moment. Your nervous system is altered by the traumatic experiences; it is reprogrammed to constantly fight with unseen dangers and scan for imaginary threats. As a result, you experience anxiety, depression, and nightmares. You are, in a way, stuck in your growth, because being constantly in survival mode and struggling to just keep yourself on the surface, your nervous system cannot fully integrate new experiences in your life.

The worst thing is that, with traumatic memories often “forgotten” and pushed into your subconscious, you just don’t understand “what’s wrong with you”. You blame yourself for your pain and suffering, and for not being able to feel “normal”. This leads to overwhelming feelings of guilt and shame. You feel like you’re going crazy…your life is experienced as fragmented and disconnected from your body and emotions.

Are we, trauma survivors, doomed to live in this miserable survival mode for the rest of our lives? According to L.R. Knost, author and children’s advocate, “Trauma and generational patterns are woven into the fabric of our lives. But they are not set in stone. Fabric can be unraveled, tears mended, knots untangled. And a new pattern can be tenderly and intentionally begun.”

The Rev. Matthew Fox, theologian and Episcopal priest, argues that “The first medicine for healing trauma and its severe effects is to acknowledge its reality, to shed light on it, to tell the truth. It is the unacknowledged trauma that is passed on as intergenerational sickness.”

My mother never spoke about her experiences. I believe this was her way of coping with trauma. As a child, I remember her sitting for hours on a chair, smoking a cigarette; I sensed her essence somehow dissolving, disappearing into the cloud of the cigarette smoke. I remember having an unclear, disturbing feeling that she was somewhere else, and – surprisingly – that her “absence” was my fault.

I only learned about the horrific details of her early life after she passed away. While clearing out her apartment, I found her secret journals and a collection of her correspondence with her family, first dated in 1945 and continuing up to 1975.

After reading these journals and letters, I realized that I needed help to process the truth that I had discovered and find out if there was any connection between “their” and my struggles.

I started seeing a therapist. With an amazing degree of insight, my therapist has been helping me understand the dynamics of my family and how the experience of trauma has been preventing me from being “fully alive”. She has been tenderly acknowledging and validating my “crazy” feelings, in the way that a healthy mother would acknowledge and validate feelings arising in her child. I didn’t have to be ashamed of my emotions anymore. This has been a critical element on my way to healing.

At present, in my fourth year of therapy, I don’t feel responsible anymore for what had been done to me as a child. I am letting go of my guilt and shame; I have become more trusting, more at peace, and more hopeful.

According to Trina A. Armstrong, theology professor and founder of The Center for Wellness Encounters, “Our growing awareness of trauma is not just good information, but information that can transform souls of persons.”

I am noticing that on my way to healing I grow in forgiveness and compassion. I have forgiven those who contributed to my woundedness as a child as I now understand how they had been wounded themselves. I have also forgiven myself for picking unhealthy survival patterns while enduring the ramifications of trauma. When I look back at what kind of mother I had been when my children were little (especially while raising my first child), I acknowledge that, similar to my mother, I did not have the inner resources to create a safe, happy environment for my offspring. The wounded inner child in me had not yet been tended to…

My new depth of compassion extends to all who struggle with ill behavioral patterns, as they most likely carry their own, often unacknowledged, load of woundedness.

According to the Buddhist monk Thích Nhất Hạnh, “When we are embracing the wounded child in us, we’re embracing all the wounded children in numberless generations of ancestors and descendants.”

We are story weavers of our generation.

May we wield our looms

with the bravest love

and the fiercest hope imaginable.

-L.R. Knost

With a curious heart open to the truth – however painful – a desire to change, and the help of a therapist when needed, you can become one of “us”.

Images courtesy of Katarzyna Czyz.

Thank you for this vulnerable story – it is so timely and reminds us of the deep costs of war and conflict and also of the hope of healing that can happen through the compassionate acts of others and God’s loving presence.

Thank you, Cindy, for your comment. It means a lot to me…

This is an important story that takes courage to tell and is a testament to your extraordinary strength and resilience!

A powerful portrayal of why genuine questions and time to truly hear the person’s given answers are critical during social – communication exchanges.